A Personal Beginning

In 2007, violist Mary Oliver and contrabassist Rozemarie Heggen invited me to write a piece for their duo incorporating improvisation. Despite my diverse experience writing chamber music, free improvising, interpreting, and working in a host of interdisciplinary formats, the request seemed odd.“Why do they want a notated piece if they are going to improvise?” I asked myself naively.“And what can my written intervention offer these perfectly self-sufficient virtuose other than needless complication?” Nonetheless I accepted the offer and worked through my prejudice, producing Apples Are Basic (Williams 2008). Questions lingering after working on this piece constitute the beginning of my journey with notation for improvisers. I would thus like to unpack them as an introduction to this dissertation, in order to highlight the transformation of my understanding of and creative approach to the field.

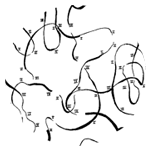

Like a child’s papier-mâché volcano filled with vinegar and baking soda, Apples was built to erupt through the combination of two oppositional forces – notation and improvisation. To this end, the score juxtaposes two types of sections: color images containing texts that correspond to “free” improvised sections, and black and white through-composed postludes in conventional notation. The images – reproductions of silkscreens by visual artist and Catholic nun Corita Kent1 – contain no literal instructions or predetermined semantic value; their role is only obliquely addressed in the legend. Performers are encouraged “not [to] think too hard about them in performance. Real improvisation is primary, and anything demonstrative or ‘composed’-sounding should generally be avoided” (“General Instructions”). Although no methods for realizing the images as notation are given, the graphic material itself is generous, transparent, and immediate. Art critic Paul M. Laporte has written of Kent’s silkscreens that “[s]ince Matisse nothing equally unproblematic and cheerful has been created (Kent 1966, inside cover), and precisely for these qualities I included them. Bright colors, verbal imperatives (“Go Slo!”, “Do not enter”), and unmistakable icons such as arrows and stop signs on the one hand, and softer colors, reflective text (sometimes hidden within images such as “In” and “Tender”), and counterintuitive angles and proportions on the other, are all meant to appeal to the improviser’s sharp, spontaneous reactivity, so bypassing the necessity of semantic clarification. (Apples thus takes advantage of the blatancy that made Corita’s work so apt for commercial advertising in the 1960s and 1970s – if to rather different ends.)

The score’s use of extended Western notation (henceforth “conventional notation”) in through-composed sections is somewhat more obscure. The material consists mostly of noisy, carefully choreographed “extended” techniques in constant movement. To articulate them every marking is essential, and therefore exhaustively explained in the legend. But despite this instructional clarity, physical parameters such as bow- and left-hand position and pressure, in combination with extreme tempi and rhythms, often “smear” the notated details or stretch apart visually continuous phrases to render gestures and audible phrases unclear. This confluence at times creates unstable and amorphous sonic results that seem to defy the specificity of the written information; it raises questions about its functionality vis à vis the apparent self-evidence of the improvised sections.

To complicate this scenario, bracketed improvisations varying in duration from 1.2” to 18” are “dropped in” the conventional notation as foreign elements, much in the same way the postludes themselves are dropped in the larger improvised fabric. Their often brief durations render any kind of flow or development within the bracketed windows practically impossible. They are nearly always preceded or followed by a rest of eight beats, which effectively relegates the improvisations to function as beginnings or endings of a written phrase. Such limitations are intensified by the fact that the bracketed sections of one player usually appear in counterpoint with the other player’s through-composed material.

My pitting the two types of notation against each other in this way was not merely a consequence of preconceptions about the general incompatibility of notation and improvisation. It was also strategic. The intention was, as suggested in my metaphor of the experiment with vinegar and baking soda, to create a situation in which the figured friction between notation and improvisation could have an unpredictable impact on both modes of performing. The impact of the friction would audibly emerge in choices made by the performers that effect the overall shape of the piece – what kind of material they play in the improvisations, how they deal with transitions, how literally they adhere to the notated material, and so on. While I had no clear idea of how this would actually sound, I hoped that this “eruption” would consist in something qualitatively different from the sum of its parts, like the volcano is from its ingredients — a new and surprising (and therefore unpredictable) musical “substance”.

What I got, however, was rather smoother. The performers’ unusually broad backgrounds in both interpretation and improvisation were partly responsible; they handily defused the tension I had attempted to build into the score. Certainly there were moments of verbal discomfort during rehearsals that stemmed from the confrontational nature of the notations. What to play during a 1.2” improvisation? How should aspects of the images like color or proportion concretely affect the improvised sections? Why does the conventional notation so relentlessly tie the players in knots? However in performance, the intended opposition of notation to improvisation tended to melt away. Hard edges between graphic and conventional notation were performed more often than not as smooth logical transitions. Paper boundaries were thus rarely audible, allowing larger temporal continuities over several pages and unexpected moments within single pages to emerge into the foreground instead. They sailed through both types of sections with equal aplomb, occasionally alluding to written fragments in improvisations, scrupulously but not slavishly adhering to the conventional notation, and supporting each other throughout. Whatever inner tension the performers experienced was either exceedingly well suppressed or never of great importance.

Despite not fulfilling my wish for eruption, Oliver and Heggen’s performance was dynamic and satisfying in many ways. In fact, it brought more out of the piece than an oppositional approach probably would have. After experiencing their “neutralizing” influence on the intended notational conflict, I began to wonder: was there ever any real potential for this dialectic of the written and the improvised to explode, or to manifest at all outside my own compositional fantasy? Eight years after writing Apples, a few reflections suggest the volcano itself was dormant.

First and foremost, as suggested above, my vinegar and baking soda were never inherently or essentially incompatible; the relationship between notation and improvisation was and is not by nature conflictual. Contrasting Apples to musics in which notation and improvisation share a perfectly fruitful, even foundational, coexistence – e.g. baroque basso continuo, Duke Ellington’s big band music, or the Chinese guqin tradition – one sees that merely juxtaposing them is not enough to create the desired reaction.

In order to develop or exacerbate points of “real” friction, I might have interrogated what is meant by “real improvisation” in the legend, or at least attempted to articulate it. The goal was to empower the players to decide for themselves what improvisation means in Apples by doing it, but I have come to feel the strategy was misplaced. How could they possibly, even as veterans of the “improvised music” scene, work with this indication? The legend encourages them not to play anything “demonstrative or ‘composed’-sounding” (“General Instructions”), but of course this is less a performance instruction than a useless tautology. As ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl has pointed out, “while we feel that we know intuitively what improvisation is, we find that there is confusion regarding its essence” (1974, 4) – even practitioners within the same tradition can have widely varying understandings of the term. In my score-based context where improvisation is negatively defined, Nettl’s observation is especially acute.

Moreover, I overlooked a cornerstone of my collaborators’ musical world view: for the improviser, who happily, skillfully, and often makes her own spontaneous music without notation, scores are simply one more artifact in the musical environment – something on or through which to improvise. To borrow from anthropologist Tim Ingold, in whose writings much of this dissertation is anchored, “there is no script for social and cultural life. But there are certainly scripts within it” (2007, 12). Improvising, for players such and Oliver and Heggen, is not an on/off switch, but rather a way of life within which other activities are nested. In positioning interpretation and improvisation dialectically, I made a category error which unwittingly emphasized the ubiquity of improvisation throughout the piece, even at the microlevel2 where it is not explicitly called for. This, in essence, strengthened points of continuity between the free and through-composed sections, undoing the opposition I attempted to construct. Had the piece been meant for repertoire-based performers, the player-notation dynamic would likely have been different – but then of course I would not have written the same piece to begin with.

Research Questions

Despite these nominal failures, the exercise of writing Apples produced a number of new, more nuanced questions from which creative possibilities, collaborations, and extended reflections have emerged ever since:

- What aspects of improvising can be fruitfully addressed through notation?

- If, for the improviser, music is fundamentally unscripted – or unscriptable – why would she compose or perform with notation at all? What kind of scripts fit in her environment?

- How does notation construct, deconstruct, or reconstruct improvisers’ relationships to each other? How do performers listen to each other differently with and without a score?

- In what ways and to what extent can notation incorporate improvisers’ unique and embodied performance practices into the compositional process?

- How can composer-improvisers use notation to share, challenge, or transform their own ways of improvising? How does this affect and transform my practice?

- How does music involving notation for improvisers encourage us to rethink the way we conceptualize and talk about musical labor?

These questions have led me over the last several years to explore a substantial, if under-documented, body of music by other artists grappling with similar issues. That work runs the gamut from Cornelius Cardew’s flagship graphic score Treatise (1970), Bob Ostertag’s posthuman funhouse Say No More (1993a; 1993b; 1996), Richard Barrett’s complex track notation in the fOKT series (2005), and Malcolm Goldstein’s meditative calligraphical tablature in Jade Mountain Soundings (1988, 63-67), to Ben Patterson’s deceptively simple event score Variations for Double-Bass (1999). The aesthetic and historical diversity here is extreme. The scores look different, different kinds of players perform them, and the music inhabits different sound worlds. Some pieces are written by non-performing composers, some by seasoned composer-performers, and some by performers who moonlight as composers. Some are formally published, some informally distributed, and some barely survived the context in which they were produced. Nonetheless from a practitioner’s standpoint they share a variety of methods and problems.

The character of these methods and problems, as well as a flavor of my own artistic and discursive approach, can be gleaned from a brief discussion of the title and subtitle of the dissertation.

On and through a Name: Tactile Paths

Tactile

The word tactile, meaning literally “of or connected with the sense of touch”3, shifts the emphasis off the visual aspect of notation – the score as object – and onto its use – what performers and composers (can) do with it hands-on in the context of realtime music-making. Two closely related but nonidentical concepts are attached to the notion of tactility: materiality and mobility. Materiality, beyond the optical or sonic matter in and of the score itself, is that quality of notation that arouses performers’ “material consciousness”, a term coined by sociologist Richard Sennett in his book The Craftsman (2008). Sennett offers “a simple proposal about this engaged material consciousness: people [craftsmen, CW] are interested in things they can change” (2008, 120). Following his proposal, Tactile Paths features music for people who use notation to change the way they play; scores give tacit, embodied performance practices plasticity, in order that composers and performers can transform them. Furthermore, I address how the meaning of these notations is often itself subject to change during performance.

Mobility arises from the fact that in order to “touch” notation, to do something with it, one cannot remain stationary. As Cardew has famously noted, “[n]otation is a way of making people move,” (1971, 99) but whereas Cardew’s statement suggests that people are otherwise static, I would argue that the improviser is always already on the move. She does not rely on the score to create dynamism; rather she uses it to modulate ongoing dynamism4 and changes it in the process. In this sense, Tactile Paths de-emphasizes the peremptory aspect of notation underlined by Cardew and instead stresses the exploration of those who work with it, both on stage and between performances, through editing or reassembling modular parts of the score.

Both senses of tactility are reflected in the coupling of players and instruments at the center of improvisation. The particular sounds and instrumental techniques represented or set in motion by a score such as those in the through-composed sections of Apples as dealt with above tend to be less important to compositional architecture than to tracing the dance of the hands, breath, ears, and instrument which is so fundamental to improvisers’ craft of feeling their way forth from moment to moment.

Paths

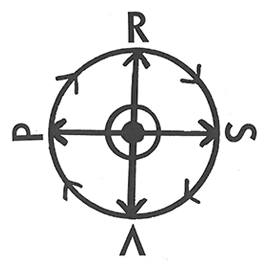

The metaphor of the path encompasses three overlapping identities of notation for improvisers: maps (printed scores), thoroughfares (invitations to collaborate), and trails (indexes of practice).

Paths are visual representations: situated maps for situated action. Rather than providing a comprehensive, bird’s eye view of the musical discourse as a basis for reproducing a preordered audible structure, scores for improvisers tend to communicate features of and within unfinished environments. The graded difference between a contemporary conventionally notated through-composed score and the scores examined in Tactile Paths might be likened to the difference between a modern architectural blueprint – completed before and outside the context of building – and the ad hoc plans of Gothic cathedrals – drawn literally on the grounds of construction sites with the aid of string and templates.5 Like this medieval variant, notation offers improvisers conceptual and material orientation in a sound world or “taskscape”6 where reading may be a form of preparation or an interface during performance.

Following composer-improviser Barrett, paths are also “invitations to collaborate” (Barrett, personal email to the author, 12 December 2015): thoroughfares of exchange between artists. These spaces for learning and sharing are made available but not contained by the maps; collaboration means traversing the path. Performers explore aspects of the environment such as bodies, instruments, technology, communities, and acoustic space, which are not represented or not representable on the page. They then feed this firsthand knowledge back onto the visual representation. Such collaborative feedback loops take place in real time as performers negotiate the meaning of signs in changing environments, and over time in collective discussion, rehearsal, and revision.

Finally, notation for improvisers may inscribe journeys taken by composers who themselves improvise. Such scores are trails – records of actual movement through a musical field7 – and not merely speculative representations or propositions. Composer-performers who trace aspects of their practice in written form (either individually or collectively) may do this for their own benefit – to externalize, challenge, and reflect on what they do in performance. But by notating they also open that practice and those reflections to inhabitation by other performers. In performing such pieces, performers dwell in the memory of composer-performers’ past performances and transform the values embedded in their tracks.

Notation

In Tactile Paths I adopt an inclusive, practice-based view of “notation”; it is neither my intention to use the term to define a field of practice, nor to use the field of practice to define the term. If definitions play any role at all here, it might be that of scores themselves: to feed back on practice and thus call themselves into question.

However, given the range of material included in the dissertation, a working definition may be helpful. We begin with pianist and artistic researcher Paolo de Assis’ formulation: “notation [is] the totality of words, signs, and symbols encountered on the road to a concrete performance of music” (2013b, 5).8 De Assis’ definition is helpful for two reasons. First, it shifts our focus onto what improvisers do with written artifacts in the greater whole of their work, and away from what they represent in an abstract or absolute sense. It underlines the view of notation as part of an ongoing process of discovery – an active journey rather than a passive reproduction. This view is something of a departure from many contemporary views on notation which converge on the idea that notation’s fundamental role is to prescribe and preserve. (More on this below in “Context – Literature Overview”.)

Second, de Assis’ flexible view of notation admits a variety of paranotational elements (or as analytic philosopher Nelson Goodman would put it “pseudonotational” elements (1968, 128)) such as sketches, post-publication edits, correspondence between composers and performers, and even post-performance reflections. These documents transmit crucial knowledge about aspects of the local improvisational practice(s) in which a given score is embedded: contingencies of personnel, occasion, technology, or instrumental technique on which its very meaning may depend.9 The extent to which notation for improvisers offloads musical work directly onto local practices without explaining them directly – which indeed for the immediate practical purposes of composers and their collaborators is usually redundant – tends to result in that knowledge being lost or forgotten for subsequent performers and scholars. (There are, of course, plenty of further example of this phenomenon in the history of pre-modern Western music; see Moseley 2013.) Paranotation provides a trace of these practices for those not directly involved in the creation of a given score, who can benefit from this knowledge in order to realize or study a given piece.

Improvisation, Improvisers, Notation for Improvisers

Defining “improvisation” – as a brief comparison of any texts that attempt to do so will show, and as Nettl’s quote earlier in this text suggested – is a notoriously difficult task. Musicologist Sabine Feisst puts the matter bluntly in her study on the term:

The term “improvisation” seems at first glance to be succinctly definable; however on closer inspection it reveals itself to be a global, amorphous, and problematic concept into which extremely diverse meanings can be subsumed, particularly since the 1950s” (1997, 1, my translation).10

In order to bypass this minefield, I approach the word improvisation with pragmatism, humility, and inclusivity, as I did in my definition of notation above. Two writers in particular have shaped my understanding of the term more than others. The first is experimental musician and scholar George E. Lewis, a seminal figure in the field of critical improvisation studies. Although he is loath to define improvisation, Lewis has on occasion made reference to “improvisation’s unique ‘warp signature’, the combination of indeterminacy, agency, choice, and analysis of conditions” (Lewis 2013). Applying the term to practices as diverse as architecture, rice farming, and the behavior of the Mars Rover, Lewis frames improvisation in terms of interactivity and attitudes rather than disciplinary norms. His modular notion of improvisation has encouraged me, as I encourage my readers, to look for the presence of its “warp signature”, or its audible trace, in unlikely places – notation foremost among them.

The second figure whose ideas have contributed to the sense of improvisation explored in Tactile Paths is anthropologist Tim Ingold. Ingold’s notion of the “wayfarer”, a kind of traveler, offers a poetic portrait of the “improviser” I have in mind in the subtitle of the dissertation:

The wayfarer is continually on the move. More strictly, he is his movement […] The traveller and his line are […] one and the same. It is a line that advances from the tip as he presses on in an ongoing process of growth and development, or of self-renewal […] As he proceeds, however, the wayfarer has to sustain himself, both perceptually and materially, through an active engagement with the country that opens along his path […] To outsiders these paths, unless well worn, may be barely perceptible […] Yet however faint or ephemeral their traces on land and water, these trails remain etched in the memories of those who follow them. (2007, 75-76)

The improvisers, or wayfarers, of Tactile Paths are neither representatives of a particular style or tradition, nor executors of a particular musical discipline, nor even necessarily performers at all. They are, in their most basic form, musicians who embrace the contingency of their environment – “the country that opens along [their] path” – and their participation – or “active engagement” – in its unfolding.11 On the surface, this characterization might appear too inclusive to be useful. But there is a temporal dimension to the wayfarer’s engagement with the country that brings my distinction into focus. The land is not simply there, to be improvised across at will; rather “it opens along his path” – it comes into being with him, and he with it. This process happens over a lifetime, not only on an afternoon’s walk. Likewise, improvisers are not improvisers merely by “making it up as they go” onstage; they continually cultivate and refine their engagement with the changing environment. They practice, listen, and reflect in the service of becoming better improvisers and change themselves and their communities12 in the process.

The intentional nature of this cultivation echoes my use of the word “embrace”: improvisers choose contingency as a creative resource.13 This is a crucial point in the context of notation which is produced by and for them. For although musical activity almost always involves some spontaneous engagement with the unforeseen, and scores are inherently unable to dictate that activity in all its actual detail, the improviser’s intentional engagement with contingency is not universally foregrounded in musical texts. Less frequently still does notation explicitly acknowledge or subject itself to the changing environment of the improviser in which it is embedded. In Tactile Paths, I compare a variety of scores that do; as we will see, the music discussed here all engages in a reflexive dialogue with the wayfarer’s prolonged embrace of contingency in some form.

Objectives and Criteria

Although they share many of the above traits, the scores I discuss in Tactile Paths are, as I mentioned earlier in the chapter, a motley bunch. They constitute neither a genre nor a tradition of their own. They include diverse forms of conventional, graphic, and verbal notations, in various degrees of formality. Artists range from performers who rarely write down their music, through composers whose work incorporates a highly refined craft of writing. Performance includes everything from seemingly conventional interpretation, to mostly free improvisation and most shades in between.

Any one or two of these facets would have been adaptable to a dissertation on a single artist or closely related group of pieces – e.g. semi-improvised solos by contemporary composer-performers; game scores by Gavin Bryars, Christian Wolff, and John Zorn; or notation as a collaborative tool in Reidemeister Move, my duo with composer-tubist Robin Hayward. So why have I deliberately chosen to examine music that looks and sounds so different, and inhabits such different social spaces?

First, Tactile Paths has a curatorial function; I wish to offer a variegated view of a phenomenon that has received relatively little scholarly and critical attention (more on this below in “Context and Literature Overview”). While the project by no means offers a systematic survey of notation for improvisers, it does represent a number of rich, interlocking perspectives. Rather than exhaustively covering a better defined corner of the field, I hope to uncover a few critical paths through these perspectives so other researchers may continue to examine and develop aspects of the practices and ideas herein.

Second, the wide spectrum serves to show how certain methodological threads transcend aesthetic and historical boundaries; my intention is to frame the threads in a way that speaks to musicians who may not necessarily identify with particular pieces represented here, or even with the very notion of notation for “improvisers”. I have in mind here curious skeptics (especially “straight” composers and interpreters, and hardcore “free” improvisers) who may wish to explore new ways of communicating with fellow musicians; to widen their spectrum of potential collaborators; or to evaluate their own practice within a broader framework than they otherwise might.

The third objective is to expand the concepts of notation and improvisation, and reveal how each might be found in the other where we least expect it. To this end I include both typical and marginal examples from the “extended family” of notation for improvisers, and explore their continuity. Work fitting unproblematically within the designation of notation for improvisers would include pieces by Barrett and Ostertag. These composers are seasoned improvisers, as are the performers who play fOKT and Say No More, the works of theirs I look at in the chapters “An Invitation to Collaborate – Répondez s’il vous plaît!” and “Say No Score”. Likewise, their scores satisfy most conventional definitions of notation.

However, I also include chapters on music by Goldstein (“Seeing the Full Sounding”) and Cardew (“A Treatise Remix Handbook”) that push conventional notions of notation and/or improvisation. Goldstein is also a seasoned improviser, but in Jade Mountain Soundings, he employs a highly detailed and prescriptive tablature notation. By examining how improvisation works at a local, physical level in this piece without the usual context of overt interactivity or the performer’s own material, I show how improvisation can be found in the basic kinesis of reading and writing. Cardew’s Treatise, a canonic graphic score with no performance instructions, and my musical essay A Treatise Remix call into question what constitutes notation. Here I show how notation obtains meaning through performance even when it is not semantically fixed a priori. I also attend to the borderline case of Ben Patterson’s Variations for Double Bass, which is more often aligned with the discourses of performance art than with improvised music, and whose “notation” consists of a barely scrutable private notebook. But what the performer does with the score clearly, if unexpectedly, reveals a powerful intersection of both notation and improvisation. By articulating what all these pieces share, I encourage readers to stretch their understandings of notation and improvisation beyond the terrain of my own examples, and to develop and connect where I may have erred or overseen.

My portrayal of the field is, as mentioned, incomplete, and I hasten to acknowledge limits and omissions. Many giants of notation for improvisers, particularly Anthony Braxton, Earle Brown, Vinko Globokar, Barry Guy, Annea Lockwood, Pauline Oliveros, Wadada Leo Smith, Christian Wolff, and John Zorn are unfortunately absent. These composers are deeply relevant to the topic, and no less worthy of attention and affection than artists included here. However many of these composers have received considerable scholarly treatment in the last years, and I am loathe to include them in a less exhaustive comparative study which would neither do them justice nor enrich the curatorial aspect of the dissertation.

A number of time-based formats are also left out, including animated scores14 on film and video by Christian Marclay, Justin Bennett, and Catherine Pancake; realtime computer-generated scores by artists such as Jason Freeman or Pedro Rebelo; and improvised conducting techniques variously known as “conduction” (Butch Morris) or “soundpainting” (Walter Thompson and Sarah Weaver). The cultures and dynamics of the moving image, technological interactivity, and the choreographic body are extremely rich unto themselves, but fall outside the purview of this dissertation.

However I do hope that artists and scholars in these areas find some value in Tactile Paths. For despite the fact that I focus on scores containing nominally fixed, atemporal marks on printed pages, I wish to underline – following semiotician Charles Sanders Peirce – that these signs only become meaningful as notation in the minds and actions of their users. Because the users are improvisers “press[ing] on in an ongoing process of growth and development” (Ingold 2007, 75), printed notation is never as fixed as it may seem. It belongs to the flux, feedback, and transformation of performance itself, and should therefore also be relevant to the forms of non-printed notation mentioned above.

Context and Literature Overview

State of the Field

Despite the large number and wide array of artists working with notation for improvisers in contemporary music, “notation for improvisers” does not – to the best of my knowledge – constitute a cohesive field of research. While neighboring areas of interest in music scholarship such as indeterminate notation, graphic and verbal notation, open form composition, improvisation studies, and the work of particular emblematic artists who use notation for improvisers (see below) overlap with the topic to a certain degree, I believe there is still a gap to be filled.

As I have stated, the principle aim of this dissertation is to change that: to articulate problems and methods that connect diverse music falling under this umbrella, and so provide both artists and scholars some conceptual tools with which to explore and discuss how notation and improvisation (can) relate in a broader sense. In order to achieve this, much of my work in Tactile Paths is creative and exegetic. I work directly with key materials, pieces, and artists, unpacking my experience of how they work in ways that run deeper than more superficial aesthetic, historical, and technical differences.

But another crucial element in this effort is to rethink views that may have hindered articulate discussion around the theme of notation for improvisers in the first place. After all, if there is such a great deal of musical practice that deals dynamically with improvisation and notation – not only in “experimental” and “contemporary” music, but also in jazz, classical music, and non-western traditions – why exactly doesn’t this music have a greater collective discursive presence?

The most obvious rationale is one I have repeated in passing several times: the aesthetic, historical, and technical differences among artists and work that could be placed in this category. Even if we restrict ourselves to the contemporary and experimental music under lens in Tactile Paths, it is far from evident what connects the music of Pauline Oliveros and Richard Barrett, Cecil Taylor and Ben Patterson, John Stevens and Annea Lockwood, or Polwechsel and the Instant Composers Pool. Not only do these artists reflect a seemingly incompatible array of styles and musico-social contexts, but their concrete approaches to notation and improvisation vary wildly. The dispersive effects of this from the outside, however, are mitigated by adopting the perspective of a practicing artist; experience composing and playing such pieces provides knowledge of phenomenological aspects that may be difficult to access through traditional (ethno)musicological methods.

Another possible explanation for this academic lacuna would be 20th century scholars’ “historical amnesia” (Sancho Velázquez 2001) regarding the presence of improvisation in Western music in general. As various scholars have noted, this gap can be attributed to a variety of factors both musical and social: “technological development and industrialization” (Moore 1992, 84), modernist compositional aesthetics (Lewis 1996), or the professed scientism of the discipline of Musikwissenschaft at the end of the 19th century (Sancho-Velázquez 2001, 228-239). However, as the very existence of these critiques shows, the field of improvisation studies has broken this barrier wide open in the last twenty-five or thirty years, happily relegating this amnesia itself to history.

In my opinion the most durable explanation for the relative invisibility of notation for improvisers as a subject in academic discourse can be traced to the contentious and variegated discourse around the nature, use, and value of notation over the last half century: what I call the prescription-preservation model of the score.

Whatever their relationship (or lack thereof) to improvisation, contemporary artists and scholars alike have often assumed that notation serves a dual function of prescribing and preserving: a score assigns the player(s) instructions with which to perform a piece of music, and stores (or alternately “describes” – see Seeger 1958 below) a piece for purposes of ownership, study, and/or subsequent performances. As The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians tells us, this is in fact the very definition of notation: “a visual analogue of musical sound, either as a record of sound heard or imagined, or as a set of visual instructions for performers.”15 Such a view is not confined to dictionaries; it is expressed implicitly or explicitly in writings by vastly different thinkers and musicians, from Nelson Goodman, proto-ethnomusicologist Charles Seeger, historical musicologist Carl Dahlhaus, composers Harry Partch and Brian Ferneyhough, editor Kurt Stone, violinist-researcher Mieko Kanno to free improviser Derek Bailey:

First, a score must define a work, marking off the performances that belong to the work from those that do not. […] What is required is that all and only performances that comply with the score be performances of the work. […] Not only must a score uniquely determine the classes of performance belonging to the work, but the score (as a class of copies or inscriptions that so define the work) must be uniquely determined, given a performance and the notational system. (Goodman 1968, 128-130)

Three hazards are apparent in our practices of writing music. The first lies in an assumption that the full auditory parameter of music is or can be represented by a partial visual parameter, i.e., by one with only two dimensions, as upon a flat surface. The second lies in ignoring the historical lag of music-writing behind speech-writing, and the consequent traditional interposition of the art of speech in the matching of auditory and visual signals in music writing. The third lies in our having failed to distinguish between prescriptive and descriptive uses of music writing, which is to say, between a blueprint of how a specific piece of music shall be made to sound and a report of how a specific performance of it actually did sound. (Seeger 1958, 184)

If one extends the concept of the written to the concept of textuality, it can be seen that […] in Western music of the past centuries the essence is still in notation. Of the three layers that were distinguished – the real-acoustic symbolized in notation, the musical-intentional as the epitome of function and meaning, and finally the layer of the interpretational means of presentation, which are also acoustically real but not notated – it is without doubt the intentional layer that matters most.16 (Dahlhaus 1979, 13, my translation)

Notes should represent, for the player, physical acts upon the strings, levers, wood blocks, or whatever vibratory bodies he has before him, but they do not represent such acts very well unless the peculiarities of his string patterns, or lever or block patterns, are taken into account as the basis for the figuration of those notes. Results would certainly be more immediate and might well be more rational as a whole if there were a separate notation for each type of instrument, based entirely upon its individuality, and, in addition, a common-denominator notation based upon ratios or clearly implying ratios. And students of the instruments would know both notations – the one for playing the music of a particular instrument, the other for studying and analyzing the total result. (Partch 1949)

I demand of notation that, first of all it be an image of the sounds required, depicted according to whatever conventions have been adopted. I demand also that it provide a tablature, that is to say, a set of instructions to the performer as to how to go about creating the required sounds – finger positions, strings, specific woodwind fingerings and so on.

I demand particularly, however, of notation that it be historically resonant in that it succeed in suggesting to the performer relevant musical contexts not amenable to highly concrete and particular notational specification. The total semantic weight of events specified, in other words, should be greater than the sum of individual instructions offered. (Ferneyhough, unpublished interview with staff of Parergon, 1997)

An editor serves as the mediator between the composer who invents new notation and the performer who must interpret it properly. A conscientious editor, one who involves himself in the musical aspect of the scores under his care, can bring the performers’ need for notational clarity to the attention of the composer and collaborate with him toward this goal. Conversely, he can elucidate to the performer some of the composer’s intentions and visions which may not be fully realized in the notation. Musical notation, after all, is not an ideal method of communication, utilizing, as it does, visual devices to express aural concepts. But it is all we have. (Stone 1980, xvii)

Musical notation in western classical music is a system which preserves past musical events while enabling and informing future ones, both describing musical works and giving specific instructions for them to be realised. We use notation for a wide variety of purposes: composers notate music for performance and publication; they sketch ideas that would otherwise be forgotten, allowing themselves time to reflect; performers read from notation to get to know a piece and also to perform it; musicologists often depend greatly on notation for analysis; and many musicians acquaint themselves with works via score-reading. (Kanno 2007, 31)

Essentially, music is fleeting; its reality is the moment of performance. There might be documents that relate to that moment – score, recording, echo, memory – but only to anticipate it or recall it. (Bailey 1992, 142)

Note the variety of historical moments, disciplines, and ideologies represented here. Note as well that each speaker has a different model of what is primarily being prescribed or preserved: for Goodman it is the musical “work”, for Partch it is practical information, for Ferneyhough it is both (plus the sediment of the work’s ontological emergence), for Dahlhaus and Stone it is the composer’s intention, and for Bailey it is the performance itself. But in each and every case, the prescription-preservation model is affirmed – it cuts across these positions.

While this model is by no means universally accepted, it evidently runs deep. So deep, I would submit, that for many people it renders the very notion of “notation for improvisers” to be a contradiction in terms, along the lines of “vegan salami” or “female masculinity”.17 Indeed if one considers prescription and preservation, both forms of fixation, to be the primary functions of notation – in ostensible opposition to the contingency and perpetual transformation of improvisation – the subtitle of this dissertation, “on and through Notation for Improvisers”, amounts to little more than an oxymoron. Drummer Edwin Prévost, never one to get mired in shades of gray, points directly to this apparent conflict when he claims

a) that in a so-called normal piece of formal music, for example a Beethoven string quartet or even a pop song, most of the technical problems of preparing for a performance are solved and refined before the intended presentation.

b) that the relationships between the musicians are mediated through the manuscript which normally represents the score.

The contrast of these analytical propositions with those of improvisation are:

a) that improvising musicians are searching for sounds and their context within the moments of performance.

b) that the relations between musicians are directly dialogical: their music is not mediated through any external mechanism such as a score. (Prévost 2009, 133)

But in notation for improvisers, there is usually more afoot and at stake; prescription and preservation may play a minor or trivial role. Cardew’s Treatise, for example, deliberately omits any explanation of the graphic notation by which one could determine an object of prescription; it accrues meaning precisely through performers’ engagement with Cardew’s refusal to prescribe. Likewise the value of the minimal verbal notation in Richard Barrett’s spukhafte Fernwirkung, written for a group of idiosyncratic improvisers assembled for a one-time event, hardly seems to consist in preservation. Rather, the object of “prescription” – different subsets of the unique constellation itself – seems to crystallize the occasion in full embrace of its immanent dissolution.

All the same, most notation for improvisers does not forego prescription or preservation entirely. Goldstein’s Jade Mountain Soundings, for instance, fits the model quite neatly in that it provides a detailed set of instructions, norms, and repeatable sonic and formal properties. However apart from framing the identity of the piece, the score also marks and catalyzes dynamic, embodied processes that can never be captured (read: prescribed or preserved) in notation of any kind. Another example can be found in Ostertag’s Say No More project, which explicitly thematizes and plays with the very notions of prescription or preservation; ironically, however, audio recordings and the memories of the performers themselves perform the bulk of this work, and written notation plays an ancillary role.

Presuming we do not take these examples’ incompatibility with the prescription-preservation model as evidence that they are in fact (as hardliners such as Goodman and Dahlhaus might argue) no notation at all, that model would thus require some adjustment. The question then becomes: what exactly is afoot and at stake in notation for improvisers besides prescription and preservation – and how can that something be generalized beyond individual pieces and performances, in order that the model might be expanded, complemented, or challenged? Addressing these questions might help not only to illuminate notation for improvisers, but also to rewire assumptions about notation and improvisation in general which have plagued scholars and practitioners across the board.

In Tactile Paths I thus draw on writers who provide ways of broadening, complementing, and challenging the prescription-preservation model. Like the artists I examine, these writers represent a wide variety of artistic and scholarly positions. The literature I use can be roughly grouped into three categories: (artists’) views on notation for improvisers, critical improvisation studies, and distributed and situated cognition.

(Artists’) Views on Notation for Improvisers

The research questions I outlined in the introduction to this text are hardly unique to my own music. One finds evidence of their importance to practitioners in a variety of texts by and about artists included in Tactile Paths, and others who could have been, such as Cardew (1961; 1971; 1974), Karkoschka (1979), Braxton (1985; 1988; Lock 2008), Brown (1986), Goldstein (1988), Eno (2004), Rebelo (2010), Barrett (2014), Smith (Oteri 2014), and Toop (2015). Understandably, most of these frame the interface of notation and improvisation in terms of the authors’ personal practices; they are not studies of notation for improvisers in general. However they are invaluable to my attempt at generalizing shared concerns for two reasons. First, they flesh out performative contexts – e.g. in what circumstances and for/with whom pieces were written, and how they have been performed and changed over time – issues which are so crucial to my research questions. Second, some of these artists offer refined conceptual descriptions of their methods, such as Barrett’s notion of “seeded improvisation” or Smith’s “Ankhrasmation”. Principles revealed in these concepts help establish links with other artists that I develop throughout the dissertation.

Two of these artists/ writers are worthy of individual commentary. Composer, pianist, and musical activist Cornelius Cardew’s three texts (1961; 1971; 1974), written at different stages in his artistic development, not only offer incisive reflections on the role of notation in contemporary music at a time of bubbling innovation; they also trace the emergence of his interest and commitment to improvisation as a partial consequence thereof. Treatise Handbook, written while he composed Treatise (perhaps the only canonical piece included in the dissertation) offers a condensed, existential perspective on this evolution, articulating questions of major significance to the entirety of Tactile Paths. I deal with these in my own “A Treatise Remix Handbook”.

Pedro Rebelo’s brief article “Notating the Unpredictable” (2010) is among the very few texts to have dealt with the topic of notation for improvisers in general, and perhaps the only one to have done so from an academic perspective. It begins with questions of explicit interest to Tactile Paths: “How, then, does the role and function of notation change with specific contemporary practices, which are by definition ill-defined and feed off fluidity and change? What is the nature of notation in distributed and collaborative practices such as improvised music or network music performance?” (17). It also provides rich examples of notation as communication, reflection, and production, beyond mere prescription and preservation. But unfortunately, Rebelo’s discussion of his own creative responses to these questions glosses over the most important aspects of the performative “unpredictability” he purports to address – what improvising performers actually do with notation. Instead Rebelo treats performance in purely general, hypothetical terms, and focuses almost exclusively on how his realtime computer-generated notation changes its appearance, rather than on how it engages those who are actually making the sounds in concert. In contradistinction to this approach, I proceed from the claim that the tension and connections between the factual contingencies of performance and notation are the heart of notation for improvisers, and only by taking them into account can research on the topic achieve Rebelo’s goal of “question[ing] the presumptions of those who write and those who read, not to create a new language but rather to agitate notational practice, to unbind the volume, and to expose liveness” (26).

By contrast, musicologist Floris Schuiling’s work (2015; 2016) on the music of Dutch composer-improviser Misha Mengelberg for the Instant Composers’ Pool (ICP) addresses performative contingency head-on. In a recent article Schuiling argues that

the scores in the ICP’s repertoire function as significant sources of creativity for the performers. Rather than establishing uniformity and reaffirming the control of a composer as in the discourse and practice of the “work-concept”, the pieces in the ICP contribute to the heterogeneity of creative possibilities open to the performers. (Schuiling 2016, 47)

Employing ethnographical methods and borrowing from exponents of “relational musicology” (Born 2010; Cook 2012), Schuiling makes a rare and compelling argument for the need to revise dominant concepts of both notation and improvisation based on what improvisers actually do with scores. He focuses on the spontaneous and collective (re)ordering of set lists; individual players interrupting a piece with fragmentary scores (or “virus” scores, in Mengelberg’s terminology); and the radical reworking of the ICP repertoire over decades through “not only varying the tempo, playing lines from other musicians, playing lines backwards, suddenly changing from minor to major, but also reinterpreting clefs, rests and the letters in titles as ‘graphic scores’” (49-50).

While Schuiling’s analysis is commendable in many respects, an important aspect of these scores is left out: the process of notating. One wonders, how did Mengelberg go about writing these pieces in the first place? Clearly they were not written for a generic orchestra or string quartet – they were written with his own improvisatory proclivities, the sizeable personalities of his bandmates, and the group dynamic and history of ICP as a whole in mind. Furthermore, given Mengelberg’s taste for disruption and juxtaposition (Schuiling 2016, 47), one can easily imagine that he changed his approach to producing notated material over time based on first-hand experience of how previous scores were performed. How, we ask, did this change manifest? Such questions, I would argue, are crucial to presenting a complete picture not only of the work of the ICP, but of all notation for improvisers.

However even in the best of circumstances they tend to escape the musicological eye (and ear). One can compare drafts, sketches, edits, and scores; read correspondence with performers; or interview composers directly. But even when robust documentation is available and artists are willing and able to share this sensitive information, the minute particulars of inscription may simply be too ephemeral or private for external observation to capture. An artist-researcher such as myself, however, is in a better position to answer these questions by unpacking first-hand experience. The tacit knowledge of writing and realizing notation offers practitioners a rich perspective on notation that complements the paleography and ethnography of traditional musical scholarship.

Critical Improvisation Studies

Given my emphasis on how improvisers use notation – both as composers and performers – rather than on the internal structure of the documents themselves, I naturally draw on the work of a number of artists and improvisation scholars who do not concern themselves explicitly with notation. These sources can be placed under the umbrella of critical improvisation studies, a nascent interdisciplinary field that seeks to understand the practice of improvisation not only in music and the arts, but across a wide range of human activity.18

Artistic Sources

Three books by practitioners are particularly important to Tactile Paths. Goldstein’s mostly handwritten anthology of scores and reflective texts Sounding the Full Circle (1988) ironically does not address notation, despite the fact that the volume contains some of the very most beautiful and provocative examples of notation for improvisers. His primary interest is the deeply material triangulation of body, instrument, and sound through improvisation summed up in his concept of Sounding, and the score is simply a tool to reach it. In “Seeing the Full Sounding”, I explore how principles of Sounding are embodied in Goldstein’s notation, folding his texts back onto his work in the form of a documentary film. The concept of Sounding also sheds light on the physicality of notation in pieces by other composers as well.

My occasional citation of (and where uncited, deference to) the second text, Derek Bailey’s flagship Improvisation: its nature and practice in music (1992), may surprise some readers. Written by an artist fighting for the legitimacy of experimental improvised music in unsympathetic times, the book tends not to celebrate notation. However, his discussions of players’ relationships to their instruments, ensemble dynamics, and especially the worldview of “long-distance improvisors” (125) are eminently relevant to my arguments about notation. Bailey’s and his interviewees’ “straight from the hip” descriptions of these phenomena help contextualize the dynamics of improvisation in which notation emerges and on which it feeds back; were he alive to read Tactile Paths, he might be delightfully shocked to see how the notated work included here extends and refines his ideas.

The third book, echtzeitmusik: selbstbestimmung einer szene / self-defining a scene (Beins et al 2011) provides artists’ accounts and theories of improvisation from within the Berlin experimental music scene of which I am a part at the time of writing this dissertation. (Geography aside, two of the editors, Christian Kesten and Andrea Neumann, were collaborators in the making of A Treatise Remix.) Beins’ (2011) chapter on group interaction and Neumann’s chapter (2011) on her self-designed inside-piano instrument and sound research, stand out for their critical first-person reflections on the brass tacks of the craft of improvisation which can be so difficult to observe from a distance. On a different note, the roundtable conversation “Labor Diskurs” (Beins et al 2011, 232) provides a bird’s-eye view of many contentious points in the discourse surrounding notation and improvisation, not only in Berlin but throughout Europe.

Scholarly Sources

Among the sundry improvisation scholars referenced throughout the dissertation, I have returned to three more than others. Two are united by their arguments for a mobile theory of musical improvisation in which the “performance according to the inventive whim of the moment”19 is not a necessary and sufficient characteristic of improvisation, but rather one among many. Benson’s The Improvisation of Musical Dialogue: A Phenomenology of Music (2003) expands the notion of improvisation within the remote domain of classical music to include a wide variety of over-time practices such as ornamentation, transcription, and compositional revision in addition to the performance of cadenzas and extemporization. In contrast to Tactile Paths, Benson’s understanding of notation in these practices is tied to limited musical materials, codified performance practices, and questions around the lives of musical works. However through this discussion he leads the reader to the view of improvisation as a meta-practice, a dialogue among composers, performers, and listeners that has much to offer my analyses of more experimental work.

Cobussen, Frisk, and Weijland’s (2010) article “The Field of Musical Improvisation”, and Cobussen’s recent book of the same name (2016), melt the discipline of improvisation to an even greater degree than Benson, characterizing it as a phenomenon that “takes place in a space between” (12) performers, composers, organizers, listeners, and many more actants. Their model is a fluid and nonlinear one in which musicians, technologies, and historical and social situations feed back on each other. Understanding improvisation, Cobussen argues, requires us to examine constantly evolving activities and networks rather than stable agents or artistic products alone. In my concept of notation as a tactile path, scores can be seen as nodes inside this dynamic field that modulate musical and social relationships, and at the same time are changed by them. Likewise, they serve as snapshots of actants in that field from the outside, affording composers and performers additional perspectives on the environments they inhabit.

Cobussen shares a taste for complex systems with two other scholars whose research on improvisation has informed my ideas around notation. David Borgo’s work drawing on theories of extended and distributed cognition, particularly his 2014 article “The Ghost in the Music: Improvisers, Technology, and the Extended Mind”, has had a formative influence on my turn toward a processual, use(r)-based view of notation. Borgo develops a view of musical cognition as being not merely in the heads of individual musicians, but rather embedded in, and to an extent continuous with, the performative environment; among other things, that environment includes instruments, technology, and other musicians. Building on that model, I treat notation non-hierarchically as another element in the cognitive system, dynamically interacting with other agents. This represents a rather radical shift from the dominant structural view of notation that Borgo critiques elsewhere:

Academic music studies have tended to argue (at least until recent decades) that music’s significance, as well as its ontological status, resides in its structural features; specifically those structural features that may be represented as a notated score. Meaning, it was assumed, was ‘in the notes’ […] For music not predicated on the primacy of a notated score or on strong distinctions between composers and performers – in other words, most music on the planet – this often meant the kiss of death, since the music academy has traditionally viewed all modes of musical expression through the formal and architectonic perspective of resultant structure. (Borgo 2007, 95)

In Tactile Paths I develop a view of notation that works for, rather than against, his theory of improvisation, and hope to offer a surprising way to enrich it.

Distributed and Situated Cognition

In addition to the above-mentioned work in the field of music, a number of writers in contemporary cognitive science20 have laid the groundwork for Tactile Paths. These scholars concern themselves with the interdependence of thought, perception, and action throughout human experience. Although I do not often refer to them explicitly, they have been foundational for my view of how notation works and changes within a dynamic musical environment, beyond simply transmitting static programs or instructions from composer to performer. (They have likewise influenced the work of Borgo and Cobussen discussed above.)

Edwin Hutchins’ Cognition in the Wild (1995) focuses on the distributed qualities of cognition in his analysis of a naval ship mishap. He argues that the knowledge required to improvise bringing the ship to harbor without its failed electronics is spread, or distributed, over the ship’s team and their texts and tools:

One can focus on the processes of an individual, on an individual in coordination with a set of tools or on a group of individuals in interaction with each other and a set of tools. At each level of description of a cognitive system, a set of cognitive properties can be identified; these properties can be explained by reference to processes that transform states inside the system. The structured representational media in the system interact in the conduct of the activity. (Hutchins 1995, 37)

In this dissertation I consider the behavior of a band or composer-performer collaboration to be similar to a naval crew in distress; both think and act as a complex organism. Musical agency can be located and analyzed in the coupling of a player and her instrument, a player and her instrument with the notation, and players and their instruments with each other and the notation. Scores are treated as “representational media” that “interact in” – not only direct – “the conduct of the activity.” I also proceed from Hutchins’ assertion that cognition is distributed over time, not only during the performance of a task. While I am neither able nor interested to apply his computational analyses to the music under lens, I embrace his keen eye for real-world contingencies as part of, rather than anethema to, the formal structure of behavior.

Lucy Suchman’s Human-Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions (2007) considers how cognition is situated, or embedded in, the structure of the environment in her discussion of users’ interactions with copy machine help menus. According to Suchman, cognition does not occur as a linear process of external perception (input), mental representation and planning (computation), and action (output) causally constrained by an agent’s surroundings. Rather, it arises from improvised interaction with those surroundings:

[T]he efficiency of plans as representations comes precisely from the fact that they do not represent those practices and circumstances in all of their concrete detail. So, for example, in planning to run a series of rapids in a canoe, one is very likely to sit for a while above the falls and plan one’s descent. The plan might go something like ‘I’ll get as far over to the left as possible, try to make it between those two large rocks, then backferry hard to the right to make it around that next bunch.’ A great deal of deliberation, discussion, simulation, and reconstruction may go into such a plan. But however detailed, the plan stops short of the actual business of getting your canoe through the falls. When it really comes down to the details of responding to currents and handling a canoe, you effectively abandon the plan and fall back on whatever embodied skills are available to you. (Suchman 2007, 72)

Suchman’s example offers a tailor-made analogy for the dynamics of notation for improvisers. Rather than writing a comprehensive program for performance, most composers plan within the performative environment in private practice, meetings with performers, and rehearsals. They give incomplete instructions that purposefully draw on the embodied skills of players not only to carry out the musical plan, but to co-construct the situation in which those instructions can become meaningful. Suchman’s articulations of the finer points of plan formation, negotiation, and the structure of their representations have been a great help to my efforts to understand the myriad ways that notation that notation is used and developed by and for improvisers.

Over the course of reviewing literature by cognitive scientists, I have however consistently run into one major incompatibility between my subject and theirs: most if not all the studies of distributed and situated cognition I have read rely on a goal-based model or experiment. In the examples described above, Hutchins’ subjects attempt to steer a ship safely to harbor; Suchman’s subjects make photocopies or get the canoe downstream without capsizing. In my opinion and experience, experimental improvisation and notation’s relationships to teleological tasks are ambiguous; the wayfarer’s vocation is to remain in movement, “press[ing] on in an ongoing process of growth and development, or of self-renewal” (Ingold 2007, 75-76). Perhaps for this reason, cognitive science has remained a background for Tactile Paths, rather than become an active discursive partner.

Dissertation Structure – Website

As a coda to this introduction, I would like to offer a few words on the structure of the dissertation. Tactile Paths is a native website. The choice of format is partly practical, with the goal of providing access to scores and recordings that are difficult or impossible to locate in research libraries and standard distribution outlets. Without these primary sources, discussion is emaciated. Additionally, I hope the internet provides a way to reach non-academic practitioners, above and beyond a readership of scholars and specialists.

The conceptual role of the website format is to reflect the content metaphorically. Tactile Paths is a discourse on notation for improvisers, but it is also a meshwork of paths through them, a “meta-notation” that the reader is invited to explore in much the same way as performers explore the scores.

The paths, or chapters, of the dissertation are ad hoc, bottom-up analyses of single pieces or small groups of related pieces. Because the spectrum of music included is rather wide, a willfully improvised methodology is adopted in order to best articulate the unique environments in which shared artistic methods and problems emerge. For this reason, they differ rhetorically, involve media in different ways and to varying degrees, and draw on different bodies of secondary literature. In this way I use the diversity and contingency of my subject as a discursive resource, taking what architectural critics Charles Jencks and Nathan Silver have dubbed an “adhocist” approach:

By bringing together various, immediately-to-hand resources in an effort to satisfy a particular need, adhocism may satisfy the particular problem with a juxtaposition of part-solutions. For example, it may be necessary to solve a problem without the ‘usual’ materials or experts […] [I]n place of experts, an emergency team, ad hoc committee, or volunteer brigade can do the work instead – sometimes using bizarre methods that notoriously prove a lesson later to those with special skills or training. (Jencks and Silver 2013, 110-111)

Thus I draw as often as possible from my – and the artists’ – own “emergency” first-hand experience as artists. In some cases this has resulted in purpose-built creative projects and presentation formats such as “A Treatise Remix Handbook” and “Seeing the Full Sounding”. These are intended not only as subjects for research, but as aspects of the research process itself. (More on this in individual paths.)

In order to provide links among the paths, the reader will find a number of topics assigned to each chapter. These are the tags, or keywords, that identify themes or sites of inquiry that link multiple artists or pieces. They constitute the territory along which paths are inscribed.

All of the paths are ordered numerically for the sake of reference and convenience, but the argument of Tactile Paths does not proceed teleologically. Rather, the reader is encouraged to move among paths and topics in any order. Each route will afford a different understanding of the landscape. The objective of this structure is thus not only to reinforce or re-present my conception of how these pieces and concerns relate, but also to offer the reader a live environment in which to experience or improvise with them firsthand. The argument that unfolds as the reader passes through the website has a parallel in Tim Ingold’s description of medieval readers’ experience of travelling through a text:

The flow, here, is like that of the contours of the land as, proceeding along a path, variously textured surfaces come into and pass out of sight. Thus the ‘stages’ of the composition are to be compared not to steps in the march of progress but to the successive vistas that open up along the way towards a goal. Going from stage to stage is like turning a corner, to reveal new horizons ahead. (Ingold 2007, 96)

Hopefully, knowledge gained from readers’ exploration of Tactile Paths will be likewise transferable to “new horizons” beyond the immediate field.

- For more information on Kent’s life and work, see http://www.corita.org.

- “Microlevel” improvisation is homologous with what philosopher Bruce Ellis Benson calls “Improvisation_1: This sort of improvisation is the most ‘minimalistic.’ It consists of ‘filling-in’ certain details that are not notated in the score. Such details include (but are not limited to) tempi, timbre, attack, dynamics, and (to some degree) instrumentation. No matter how detailed the score may be, some – and often much – improvisation of this sort is necessary simply in order to perform the piece.” (2003, 26) Negotiating notated and “filled-in” details in Apples can be particularly problematic because of the large gap between highly specific notation and unruly instrumental techniques. Not surprisingly (and to the benefit of the piece), Oliver and Heggen generally favored technical unruliness over written structure and on several occasions allowed such “indeterminacy” to continue and form part of the bracketed improvisations (see Mary Oliver’s section IV solo at 4:55, or the duo’s transition from section V to VI at 7:00). These moments constitute windows on the ineluctible continuity between the notated/improvised poles I had attempted to construct.

- Oxford Dictionaries, s.v. “tactility”, accessed 12.12.15, http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/tactile?q=tactility#tactile__7.

- Richard Barrett: “[M]y involvement with combining notation and improvisation hasn’t begun from taking a notated composition as a default position and ‘opening up spaces’ for improvisation within it, but instead from free improvisation as a starting point, and using notation not to restrict it but to suggest possible directions or possible points of focus for it.” (2014, 62)

- See Turnbull 1993.

- Tim Ingold’s term “taskscape” refers to a “qualitative and heterogeneous […] array of related activities […] grounded in the ‘rhythms, pulsations and beats of the societies in which they are found’.” (2002, 195) Ingold’s distinction is useful to understanding the notation of actions which defer to the “ensemble of tasks” (195) in which the improviser is perpetually engaged (rather than construct individual tasks in abstraction), and to her embeddedness in “social time” (195) (rather than an external temporal grid).

- My use of the word “field” denotes the landscape of improvised musical practices through which the tactile paths of this dissertation are traced. Following Cobussen, Frisk, and Weijland (2010), I consider the “Field of Musical Improvisation” to be a “space of interaction” not only directly “between humans or between musicians and sounds,” but also with the past through the medium of notation.

- Although De Assis writes from the perspective of a repertoire pianist rather than that of an improviser per se, his critical view of the notion of “interpretation” and his emphasis on the role of “experimentation” in the performance of through-composed music (2013a) overlap with my emphasis on materiality and dynamism in the performance of notation for improvisers. The fact that a repertoire-based performer and scholar, rather than an improviser, offers the most useful definition of notation for my purposes underlines that the practices I investigate are not, as a class, categorically distinct from “conventional” performance of Western concert music.

- For example, Cardew’s Treatise Handbook (1971) and a postlude to Goldstein’s Jade Mountain Soundings (1988, 68) detail the two composer-performers’ empirical discoveries after playing these pieces. Their critical reflections not only serve as supplementary “tips” to prospective performers, but actually expand or change the meaning of information (not) included in the original “core” notation. Likewise, Ben Patterson’s handwritten edits and markups in his self-published copy of Variations for Double-Bass (1999) open up a world of possibilities for the improvising performer that are difficult to ascertain from the “clean” copy of the score published in his catalog of event scores (Stegmayer 2012).

- “Der Terminus ‘Improvisation’ scheint sich auf den ersten Blick kurz und bündig zu lassen, doch erweist er sich bei genauerer Betrachtung bald als globaler, amorpher und problematischer Begriff, dem seit den fünfziger Jahren in verstäktem Maße sehr unterschiedliche Bedeutungen subsumiert wurden.” (Feisst 1997, 1)

- In this sense, many kinds of contemporary musicians and artists could be considered improvisers: not only self-appointed “free improvisers”, but also phonographers, rock or jazz musicians, studio producers, designers and takers of sound walks, Fluxus artists, classical musicians, or non-performing composers.

- See Fischlin and Heble 2004 and Born 2017.

- This choice can be aligned both with Lewis’ notion of improvisation’s “warp signature” (2013) mentioned above, and with organizational scholar Erlend Dehlin’s notion of “positive (proactive) improvisation” as opposed to “negative (reactive) improvisation” in the workplace (2008, 223). Like Dehlin I consider the practitioner’s understanding of improvisation as “an attitude or as a method of practical thinking”, rather than a distinct category of practice, but I do not share his focus on spontaneity and novelty as pillars thereof. My reluctance is based on both personal experience and on the historical connection of spontaneity and novelty to Romantic ideals that is by and large irrelevant to the music of Tactile Paths. As a scholar of business organization rather than music, Dehlin, of course, need not contend with this baggage.

- For a bibliography of “animated scores” see http://graphicnotation.com.

- Grove Music Online, s.v. “notation”, accessed 02.03.16, http://oxfordindex.oup.com/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.20114.

- “Erweitert man aber den Begriff der Schriftlichkeit zu dem des Textes, so zeigt sich, daß eben doch […] in der europäischen Musik der letzten Jahrhunderte das Wesentlich in den Noten steht. Von den drei ‘Schichten’ die unterschieden wurden: der akustisch realen, die durch die Notation symbolisiert wird, der musikalisch intentionalen als Inbegriff von Funktionen und Bedeutungen und schließlich der Schicht der interpretatorischen Darstellungsmittel, die wiederum akustisch real sind, aber nicht notiert werden, ist es zweifellos die intentionale, auf die es ankommt.” (Dahlhaus 1979, 13)

- See gender theorist Judith Halberstam’s Female Masculinity (Halberstam 1998).

- See Lewis and Piekut 2014, Borgo (n.d.), and the online journal Critical Studies in Improvisation/ Études Critiques en Improvisation http://www.criticalimprov.com.

- Oxford Dictionaries, s.v. “improvisation”, accessed 29.08.16, http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199578108.001.0001/acref-9780199578108-e-4586.

- Aside from Hutchins 1995 and Suchman 2007, both described below, see Clancey 1993; Kirsh and Maglio 1994; Chiel and Bier 1997; Clark and Chalmers 1998; Anderson 2003; Noë 2004; and Gallagher 2005.

References

- Anderson, Michael L. 2003. “Embodied Cognition: A Field Guide.” Artificial Intelligence 149 (1): 91–130.

- Bailey, Derek. 1993. Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice in Music. Boston: Da Capo Press.

- Barrett, Richard. 2005. fOKT. Unpublished score.

- ———. 2014. “Notation as Liberation.” TEMPO 68 (268): 61–72. doi:10.1017/S004029821300168X.

- Beins, Burkhard. 2011. “Scheme and Event.” In Echtzeitmusik Berlin: Selbstbestimmung Einer Szene | Self-Defining a Scene, edited by Burkhard Beins, Christian Kesten, Gisela Nauk, and Andrea Neumann, 166–181. Hofheim: Wolke Verlag.

- Beins, Burkhard, Christian Kesten, Andrea Neumann, and Gisela Nauk, eds. 2011. Echtzeitmusik Berlin: Selbstbestimmung Einer Szene | Self-Defining a Scene. Hofheim: Wolke Verlag.

- Benson, Bruce Ellis. 2003. The Improvisation of Musical Dialogue: A Phenomenology of Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Borgo, David. n.d. “Entangled: The Complex Dynamics of Improvisation.” https://www.academia.edu/22893440/Entangled_The_Complex_Dynamics_of_Improvisation.

- ———. 2007. “Musicking on the Shores of Multiplicity and Complexity.” Parallax 13 (4): 92–107.

- ———. 2014. “The Ghost in the Music: Improvisers, Technology, and the Extended Mind.” https://www.academia.edu/1337731/The_Ghost_in_the_Music_Improvisers_Technology_and_the_Extended_Mind.

- Born, Georgina. 2010. “For a Relational Musicology: Music and Interdisciplinarity, Beyond the Practice Turn: The 2007 Dent Medal Address.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 135 (2): 205–243.

- ———. 2017. “After Relational Aesthetics: Improvised Musics, the Social, and (Re)theorising the Aesthetic.” In Improvisation and Social Aesthetics, edited by Georgina Born, Eric Lewis, and Will Straw. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Brackett, John. 2010. “Some Notes on John Zorn’s Cobra.” American Music 28 (1): 44–75.

- Braxton, Anthony. 1985. Tri-Axium Writings. 3 vols. Middletown, CT: Synthesis Music.

- ———. 1988. Composition Notes. Middletown, CT: Synthesis Music.

- Brown, Earle. 1986. “The Notation and Performance of New Music.” The Musical Quarterly 72 (2): 180–201.

- Cardew, Cornelius. 1961 (2006). “Notation – Interpretation, Etc.” In Cornelius Cardew: A Reader, edited by Edwin Prévost, 5–22. Essex: Copula.

- ———. 1970. Treatise. London: Hinrichsen Edition, Peters Edition Limited.

- ———. 1971 (2006). “Treatise Handbook.” In Cornelius Cardew: A Reader, edited by Eddie Prévost, 95–134. Essex: Copula.

- ———. 1974 (2006). “Stockhausen Serves Imperialism.” In Cornelius Cardew: A Reader, edited by Eddie Prévost, 149–227. Essex: Copula.

- Chiel, Hillel J., and Randall D. Beer. 1997. “The Brain Has a Body: Adaptive Behavior Emerges from Interactions of Nervous System, Body and Environment.” Trends in Neurosciences 20 (12): 553–557. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01149-1.

- Clancey, William J. 1993. “Situated Action: A Neuropsychological Interpretation Response to Vera and Simon.” Cognitive Science 17 (1): 87–116.

- Clark, Andy, and David Chalmers. 1998. “The Extended Mind.” Analysis 58 (1): 7–19.

- Cobussen, Marcel. 2016. The Field of Musical Improvisation. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Cobussen, Marcel, Henrik Frisk, and Bart Weijland. 2010. “The Field of Musical Improvisation.” Konturen 2 (1): 168–85. doi:10.5399/uo/konturen.2.1.1356.