Notation is an invitation to collaborate.1

In the planning of communities a score visible to all the people allows each one of us to respond, to find our own input, to influence before decisions are made. Scoring makes the process visible.2

Collectivity is almost universally recognized, and celebrated, as a cornerstone of improvised music. Group interaction onstage is itself a crucial feature for listeners; how materials and events emerge from socially situated actions and reactions between performers is often viewed as at least as important as the sounds and sound-forms that they produce (Monson 1996; Fischlin and Heble 2004; Haenisch 2011). The values that underlie and evolve through these interactions (MacDonald and Wilson 2005) can anchor communities that form around improvised music; the notion of improvisation as a “practice of conversing as equals” (Nicholls 2012, 114), in which difference is both interrogated and respected, has often been cited as an instantiation of and a model for self-determination and social change (Fischlin and Heble 2004; Lewis 2008; Prévost 2009; Born 2017).

Notation need not be a part of these models of collectivity per se. As anthropologist and former musician Georgina Born has argued,

there is perhaps something singular about improvisation in that improvised performances are marked by degrees of openness, mutuality and collaboration that are heightened and intensified when compared with the interpretation of scored works, and that necessitate participants’ real time co-creation and negotiation of social-and-musical relationships. From one perspective, then, such performances may become sites for empractising ways of ‘being differently in the world’ based on a ‘recognition that alternatives to orthodox practices are available’ (Fischlin and Heble, The Other Side of Nowhere 11). (Born 2017, 50)

Some scholars who emphasize the political dimension of improvisation, such as philosopher Tracey Nicholls, even suggest that notation is incompatible with true collectivity:

I want to highlight two ways in which improvisatory practices and principles of improvisation can be put into practice in a political context: we can affirm that we always have available to us the option of rejecting the preconceived instructions of a score or script; and we can commit ourselves to the practice of conversing as equals. Whatever its other limitations, improvisation is necessarily and integrally resistant to the perceived authority we attach to planning and tradition and this serves as a model for countering hegemony in all forms. In departing from composed scores, it stresses the principle that there is no one right way to do things. For this reason, improvisation can be a liberatory political model at least to the extent of showing that scores (understood here as performance instructions from those who hold power) need not be followed to their bitter end, that creative community-building strategies may be substituted in place of a (partially) determining text. (Nicholls 2012, 114)

Yet music by a number of improvisers who use notation does in fact privilege and make an essential feature of collectivity. All of the artists included in Tactile Paths, as well as others such as Anthony Braxton, Chris Burns, Barry Guy, George E. Lewis, Misha Mengelberg, Pauline Oliveros, Polwechsel, Wadada Leo Smith, and John Zorn, are among them. In this music, both the non-hierarchical interaction of the group and the practice of scoring enable musical experiences that are unthinkable through only one method or the other. Furthermore, some of these artists owe the development of their work in large part to their participation in formal collectives and tightly knit musical communities: Braxton, Lewis, and Smith are lifelong members of the Chicago-based AACM (see Lewis 2008); Cardew was a member of the seminal ensemble AMM and a founder of the Scratch Orchestra (see Cardew 1969); and Zorn remains an emblematic figure of the “downtown” NY scene which blossomed in the early 1980s (see Lewis 1996 and Brackett 2010). Empirically speaking, notation and the “liberatory political model” of improvisation do not seem fundamentally opposed to each other after all.

But the above statements by Born and Nicholls do raise important questions. What is the value of notation for collective improvisation, exactly? How does notation construct, destruct, deconstruct, or reconstruct improvisers’ relationships to each other? What does notation for improvisers say about collective improvisation in the world, about “the individual as a part of global humanity” (Lewis 1996, 110)?

I would like to offer a tentative, speculative response here based on the work of two artists and thinkers who have made the collective and political aspects of notation for improvisers a primary feature of their work: visionary American landscape architect Lawrence Halprin (1916-2009) and British composer-improviser Richard Barrett (1959). Putting together their statements at the heading of this chapter, along with others which I will address throughout this chapter, we have a simple but provocative hypothesis:

Score + Response = Collaboration = Liberation.

In the following text I will explore the particulars of this proposal in the context of their own work and see how it holds up.

Lawrence Halprin – RSVP Cycles

The RSVP Cycles: Creative Processes in the Human Environment (Halprin 1969) is somewhere between a theory, a manifesto, and a metascore for score-based collaboration by Lawrence Halprin. Though not listed as an author, his wife and collaborator Anna Halprin, reluctant godmother of the postmodern movement in dance, was also deeply involved in the publication – and remains, at age 96, an exponent of its principles (Worth and Poyner 2004). Due largely to the confluence of the Halprins’ backgrounds, the book is explicitly interdisciplinary in nature. As Liana Gergely has argued in her 2013 study of Anna Halprin’s historic dance piece Ceremony of Us (1969), the cycles’ processual nature makes them ostensibly applicable to any field. This is reflected in the diversity of its abundant exemplary material; this “outrageous and seductive scrapbook of cherished images” (Kupper 1971) contains “scores” ranging from Hopi petroglyphs and player piano rolls to American football plays and vegetation maps.

Here I would like to explore the model’s creative and theoretical relevance to notation for improvisers. My primary motivation for doing so is Lawrence Halprin’s focus on the collective element, which, as I claim above, is a basic facet of musical improvisation. But over and above this general connection, Halprin’s book resonates with Tactile Paths in not aiming to circumscribe notation from the outside; rather, in the vein of Patterson’s Variations for Double-Bass, it stimulates speculative reflection to be acted upon. As Halprin states, the “RSVP Cycles and the point of scoring are not meant to categorize or organize, but to free the creative process by making the process visible” (1969, 3). In my following exposition of the RSVP cycle, I will concentrate on those aspects of the model that bear out Halprin’s claim, with an eye on its applicability to a series of pieces by Richard Barrett entitled fOKT (2005).

Structure and Examples

According to Halprin, The RSVP Cycles3 began “as an exploration of scores and the interrelationships between scoring in the various fields of art” (Halprin 1969, 1). However, reconsidering the importance of preparation and context for score production led Halprin ultimately to examine “nothing less than the creative process – what energizes it – how it functions – and how its universal aspects can have implications for all our fields” (2). The RSVP Cycles therefore do not model the practice of scoring per se, but rather the collaborative production and use of scores.

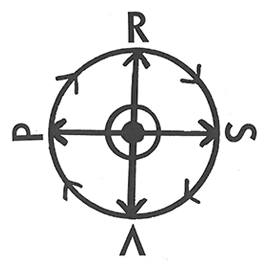

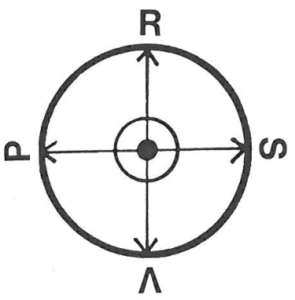

The model is based on four elements: Resources (R), Scores (S), Valuaction (V), and Performance (P):

Resources which are what you have to work with. These include human and physical resources and their motivation and aims.

Scores which describe the process leading to performance.

Valuaction which analyzes the results of action and possible selectivity and actions. The term “valuaction” is coined to suggest the action-oriented as well as the decision-oriented aspects of V in the cycle.

Performance which is the resultant of scores and is the “style of the process”.

Together I feel that these describe all the procedures inherent in the creative process. […] Together they form what I have called the RSVP Cycles. (Halprin 1969, 2)

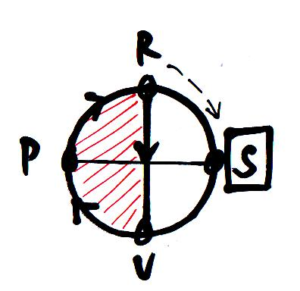

The cycles in which the elements relate is represented by a circular diagram, which

operates in any direction and by overlapping. The cycle can start at any point and move in any direction. The sequence is completely variable depending on the situation, the scorer, and the intention. (Halprin 1969, 2)

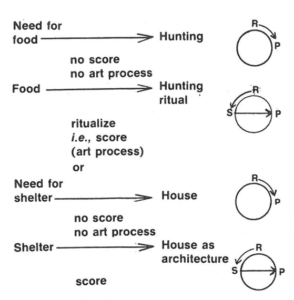

Halprin offers a simple example by way of basic universal human needs. As most of his examples, they are not without problems (see my discussion of Bach and Amirkhanian below); nevertheless this particular example does serve my purpose of fleshing out the cycles’ atomic principles:

(R) Need for food → (P). Hunting. No score no art process.

(R) Need for food → (S) → (P). Hunting Ritual. Ritualize i.e., score (art process).

(R) Need for shelter → (P) House. No score no art process.

(R) Need for shelter → (S) → (P). House as architecture. (Halprin 1969, 193)

As one can see, what Halprin calls “scores” comprises a bewildering variety of texts. This can be confusing, but in fact there is a tie that binds. As architecture critic Kathleen John-Alder points out,

[a]ccording to Halprin, scores conveyed information that guided and controlled “the interactions between elements such as space, time, rhythm, sequence, people and their activities”. As such, they illustrated how to make or act at a particular moment or place. (John-Alder 2014, 58)

Differences between particular scores and their attendant creative processes are distinguished according to various factors: what elements of the cycle are present; the degree of overlap among them; where a given process begins; and its route through the diagram. Through these factors, the model makes visible what scores do – their effects on the whole creative process. For Halprin, an important consequence of visualizing scores’ behavior is the ability to identify whether scores “energize” processes, or “describe or control” them (191). He designates four common mapping types that reveal differences along these lines:

There are many interrelationships and weightings of the cycle but the major configurations are as follows: these describe the relationship during performance (P), not during the scoring itself or what has led up to the score.

Relationships during Performance

1. (S)→ (VPR): Closed score for complete control – score as vehicle – as precise as possible to accomplish a mission.

2. (S) → (R): No control during performance – score energizes

3. (PRS): Some control, very little feedback or selectivity during performance.

4. (R) ↔ (V) / (S) ↔ (P): Some: control, selectivity, feedback, change, growth (Halprin 1969, 192)

For artists and scholars working with notation for improvisers, these “major configurations” are extremely promising in themselves. They offer a gradated view of prescription and preservation, as well as a view of what lies beyond the work. Unfortunately, however, Halprin’s musical applications of this typology – and the cycle as a whole – are extremely problematic, if not to say glib. Halprin’s concept of scoring is highly sophisticated, but he seems to be out of his depth when it comes to practice. This becomes clear in his discussion of Paul Klee’s graphic interpretation of an uncited passage by J.S. Bach:

The Bach notation is as precise and controlling as he could make it, what was left for the performer was a matter of technique and interpretation. […] Bach reaches out over the centuries to our time and prefigures what should happen with intricate precision. Basically no interaction is possible – the performer plays what is there with a greater or lesser degree of talent – he is a technician rather than an artist, a medium rather than a contributor. (Halprin 1969, 12)

It hardly seems necessary to point out the holes in this assessment, but let me a list a few for the sake of argument. First, Halprin ignores the role of history; neither changes to the score through centuries of editing (particularly Klee’s own renotation) nor the improvisatory aspects of baroque performance practice such as ornamentation are taken into account. Second, he imposes a modern work-based view of the score (i.e. as a transparent representation of the composer’s intentions) onto a practice which existed over a hundred years before this model even appeared (see Goehr 1992). Third, he erases the agency of the performer entirely, comparing her to the mechanism of a player piano: “The ultimate development of this kind of controlling musical score in which the performer is a medium, is the punched rolls used in player pianos” (13). In fact, he maps both the Bach and player piano examples identically as (S) → (VPR): “controlling”. How can Halprin’s reading account for the fact that Bach’s music was partly copied by his wife, Anna Magdalena Bach? Or for wide differences between performances of the Bach cello suites by – as just an example – Pablo Casals, Mstislav Rostropovich, and Anner Bylsma? Needless to say, this is not a fair representation of Bach’s score or its performance.

His discussion of Serenade II Janice Wentworth (Halprin 1969, 14-15), a series of graphic scores for indeterminate performer (musical or otherwise) by composer Charles Amirkhanian, is only slightly less problematic. “The scores indicate,” according to Halprin, “how the new music has influenced the scoring technique, and the score itself has responded to the requirements of the music as an open environmental event” (14). This description is justified by Amirkhanian’s subsequent list of possible interpretations by a percussionist, a painter, or a theatrical director; all performers use the score’s unexplained symbols as stimuli to unprescribed actions within the framework of their respective tools and skill sets. Halprin contrasts this “openness” to Bach, but rather incongruously maps Serenade as (S) → (P): “energizing”. Energize it does, but where is the (V) of the performers’ fundamental decisions regarding the score’s indeterminate aspects? Valuaction seems to be the crux of his distinction between the two musical examples, but it is not articulated.

In both of these cases, Halprin sells his cycle short. He only considers what the score itself denotes – from an underinformed point of view, at that – and not the life of the score in the world that his own model makes visible. For example, his application of the same mapping type to Bach and Labanotation (a choreographic scoring system used in ballet and modern dance, 40) obscures the fact that the latter is used to record pieces after they are composed and performed, whereas the former is a medium of communication with the performer before performance. One objectively transcribes, the other subjectively inscribes. Halprin’s own diagram has the potential to show this difference: he would simply need to trace a longer trajectory through the circle such as (R) → (P) ↔ (V) → (S) for the first performance of a choreography and its transcription into Labanotation, then (S) → (V) → (P) for subsequent performances. In the case of Bach, he might have included feedback between (V) and (R) to show that the performer is also in dialogue with the resources of performance practice, instrumental technique, and the perpetually evolving identities of the works that the score (partially) represents.

In a similar way, the reductive examples of the Bach and Amirkhanian scores forego opportunities to highlight surprising similarities between them. Going past the first iteration of the cycle – a single hypothetical performance – might show, for instance, that repeated performances of Bach (P) constitute a personal history with the piece (R) that a performer may consciously vary or improve (V) over time. Such change would reflect an opening in the process of interpretation, which Amirkhanian’s score shares. This oversight is all the more surprising given Halprin’s repeated emphasis on the temporal process: “The element of time,” he says, “is always present in scores. Scores are not static; they extend over time” (190).

Halprin’s (non)mapping of improvisation also begs for revision. Many of the scores he discusses involve improvisation overtly in some capacity (e.g. an Allan Kaprow Happening (30) or Anna Halprin’s dance piece Ceremony of Us (200)). However, Halprin seems not to identify them as improvisatory, reducing improvising to a monad, (P):

[I]t is important for anyone working with the cycle to understand where he is concentrating and which parts are operating. If, for instance, you jump immediately to Performance (P), you are improvising. There are times when improvisation, for example, or spontaneous responses are vital to the release of creative energies which might remain locked up otherwise. But these energies can often fruitfully lead back into the rest of the cycle or remain isolated for their own sake. (Halprin 1969, 3)

Here again he occludes the potential of the cycle by not examining his object in critical detail; he defaults to a romantic notion of improvisation rooted in an aesthetics of spontaneity and inwardness (see Sancho-Velásquez 1999, 32-35). Nowhere does he mention how improvisation might arise from negotiating (R), (S), (V), or from feedback among them. More strangely, given the collaborative foundation for the whole RSVP model, he locates improvisation at the level of the individual rather than the group. His portrayal bears an uncanny resemblance to a view of improvisation criticized elsewhere in detail by Bruno Nettl:

Specifically or implicitly accepted in all the general discussions [of improvisation] is the suddenness of the creative impulse. The improviser makes unpremeditated, spur-of-the-moment decisions, and because they are not thought out, their individual importance, if not of their collective significance, is sometimes denied. (Nettl 1974, 3)

In sum, Halprin’s analyses of music – and of others’ work in general – tend not to do justice to his model. But all is not lost.

The Sea Ranch

One gets a much richer sense of the potential of the cycles from the documentation of Halprin’s own collaborative projects, in which the entire R-S-V-P sequence is consciously deployed as a creative method. An excellent example is The Sea Ranch (Halprin 1969, 122-155), an ecological planned community in northern California, whose masterplan Halprin oversaw in the early 1960s. Although Halprin does not map the project’s evolution explicitly onto the RSVP Cycle, his annotated photos, scores, and allusions to the cycle in particular stages make it possible, with the help of secondary literature on the project, for others to infer its workings.

I will now unpack this robust example of the cycle in order to offer the reader a more charitable view of the dynamics of Halprin’s model. In addition to illuminating the structure of the model, I hope my explanation supports Halprin’s claim that the book itself is a score (Halprin 1969, “Acknowledgements”), and “[f]or a score to function the participants in a score must exhibit a commitment to the idea of scoring and be willing to ‘go with’ the specific score” (190). In other words, rather than apply the model as a finished, self-contained system, I will improvise with it in an attempt at a temporally distributed theoretical collaboration.

For purposes of structural clarity, I will proceed in outline form rather than in narrative prose.

1. Resources

- Commission by owners and developers: “Oceanic Properties, a subsidiary of the Hawaiian developer Castle & Cook, selected Halprin to oversee the master plan for a second-home community” (John-Alder 2014, 55).

- Team included cultural geographer Richard Reynolds (John-Alder 2014, 55); San Francisco Bay Area-based architect Joseph Esherick; Berkeley-based architecture firm Moore Lyndon Turnbull Whitaker (Canty 2004, 23); and “a then unprecedented wide range of disciplines: foresters, grasslands advisors, engineers, attorneys, hydrologists, climatologists, geologists, geographers, and public relations and marketing people” (Canty 2004, 23).

- Natural conditions of the site: undeveloped coastal land 120 miles north of San Francisco near the San Andreas fault; cool, damp, windy climate; active ocean; rolling meadows; patches of redwood forest.

- Historical conditions of the site: “The specific character of the landscape Oceanic purchased was the result not only of geological forces, […] but of decades of farming, ranching, and lumbering. Over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries there had been selective clearing for timber, hedgerows had been planted to protect livestock from the wind, and the meandering State Highway 1 was constructed stretching along the base of the range.” (Lyndon and Alinder 2004, 19)

- Inspiration by local architecture, especially “timber framing of local barns” along the Coast Highway (Lyndon 2009, 84).

- Explicit wish to work with ecological scoring (Halprin 1969, 117).

- Explicit wish to create “‘an opportunity for people to form a community.’ His thinking about The Sea Ranch was influenced by his experience in a Kibbutz.” (Canty 2004, 25)

- A “feeling that this area could be a prototype of how man could plan development with nature rather than ignore her” (Halprin 1969, 117).

2. Performance

- Site study: “A year of careful ecological studies revealed a great deal about the land that was not apparent from the start” (Halprin 1969, 117-118).

- Reynolds measured wind and other meteorological conditions of area (John-Alder 2014, 55).

- “Up in the woods forestry practice was studied at length” (Halprin 1969, 118).

3. Scores

- Representations of (P) such as:

- Vegetation and soil (Halprin 1969, 125).

- Topography and drainage (126).

- Wind deflection (127).

- Bioclimactic needs (128).

- Radiation impact (128).

- “A careful logging program” and “a carefully organized program of controlled burns” to rehabilitate the nearby redwood forests (118).

4. Valuaction → Resources

- Discussion of discoveries in (S) – that which was “not apparent from the start” (Halprin 1969, 117-118). This led to

- “Resource analysis” (Halprin 1969, 124) – reevaluation of (R) before proceeding with development planning.

- Example: “the cool, damp climate was outside the human comfort zone. The data also indicated that wind was the most easily controlled climate variable” (John-Alder 2014, 56).

5. Scores (↔ Resources) → Valuaction

- “Thematic early scores” (Halprin 1969, 130): development sketches (130-131).

- Visual descriptions of architectural principles to cope with wind and dampness: slanted roofs, placing buildings adjacent to hedgerows (135).

- Visual descriptions of urban planning principles to foster community living: condominiums and clustered housing (141).

- Primary purpose NOT to prescribe unilateral action (as blueprint) and preserve instrumental data about the environment for construction.

- RATHER to provide points for discussion among collaborators about how to integrate the development with the environment as a whole: “Taking particular elements and scoring alternatives as test runs to disclose options and allow for valuaction and selectivity to operate” (124).

- Contains questions regarding (R): “Stable of archt’s? – no review of aesthetics – archt’s to do their own ‘thing’. Materials?” (130)

- John-Alder:

Scores, defined as a “system of symbols”, energized the process. […] Halprin also used scores to investigate alternative design scenarios. In other words, he was again directing his colleagues to look at processes of formation for design inspiration. But unlike his earlier natural history directives, with their emphasis upon the physical mechanics of geology and physiology, this time Halprin promoted a set of generative parameters that intermingled people, their actions, and their chance encounters with natural processes, their actions, and their chance events. (John-Alder 2014, 58)

6. Valuaction ↔ Scores

- “Concept Alternatives” (Halprin 1969, 132): a grid mapping the aesthetic, social, and structural aspects of various building options, for discussion.

- “Followed hard on the heels of thematic scores and made selections between various alternatives based on values and congruence with motivations. Feedback between V and scores was continuous during this period” (124).

- Not only filtered scores for implementation in performance, but also catalyzed new scores.

7a. Scores → Valuaction

- “Location score” (Halprin 1969, 132), featuring urban policy proposals, “establishes major ‘lines of action’ for performers to follow” (138). Would later, after subsequent iterations of (V), be used as the basis for actual construction plans submitted to the property owners (141).

- Same time phase as 7b.

7b. Scores → Resources

- Drafts for ecoscore (Halprin 1969, 122-123):

The procedure began with sketches that established geologic time as the baseline metric for change. This was paired with a chart that catalogued human interaction with the land. Information included the ethnographic observations and bioclimatic analyses done by Reynolds, the development of these observations into built form, and the economic imperatives driving second home development and real-estate sales (figure 16). The next drawing organized this information into a series of parallel chronologies, or subsystems that tracked changes in geology, vegetation, and land use activity (figure 17). The final iteration, which is the ecoscore in The RSVP Cycles, transformed the parallel trajectories into a single, multi-dimensional spiral consisting of temporally distinct, but spatially overlapping rhythms. In this hypothetical landscape, layers of time and process fold back around and become a recursive feedback loop that links land use to its environmental impact. (John-Alder 2014, 28)

- Did not lead to (P), i.e. construction, but rather looped back to (R):

The ecoscore is a description of processes leading to the inventory items (R) analyzed as the basis for planning. It should of course be clear that an ecoscore does not stop at a particular point in time, but is continuously evolving. (Halprin 1969, 124)

- Reflective tool for future consideration.

8. Performance

- “Ground was broken in 1964 for three demonstration projects: a ten-unit condominium by MLTW, who prepared a plan for eleven more to be strung along the south shore of the site; a set of six ‘Hedgerow Houses’ by Esherick in a meadow; and a store near the condominium, also by Esherick.” (Canty 2004, 25)

- Construction of first phase of development.

9. Resources ↔ Valuaction

- Construction (P) led to salable product (R).

- Unexpectedly high demand: “The place took on a special cachet. Oceanic had helped to sell one hundred lots the first year but met its goal in just over eight months.” (Canty 2004, 29).

- Tension between Halprin’s scores and owners’ commercial goals:

In some respects, the growing pains of success proved a challenge. The original planning principles proved surprisingly fragile. After just five years of construction, Halprin complained that houses going up in 1969 were being “scattered” on the meadows rather than clustered along the hedgerows. Moreover, houses were being built in the front rows of shore front and forest, areas where they were forbidden by the plan. […] In part, such departures from the plan resulted from a virtual revolt by the real estate agents of Castle & Cook. They objected to not being able to market the most desirable home sites and claimed that condominium units and cluster housing were difficult to sell. (Canty 2004, 29)

10. Performance ↔ Valuaction

- “Oceanic dismissed Halprin and the original architects in the late 1960s.” (Canty 2004, 29)

- Corporate allies also left:

Boeke [vice-president of Oceanic] himself left at year’s end 1969, and one of Oceanic’s real estate agents took his place. […] Few were left in the company who cared about The Sea Ranch, and an agent was sent over to arrange Oceanic’s phased withdrawal from the project. (Canty 2004, 29)

- Subsequent developments did not reflect principles of Halprin, his collaborators, and their scores.

- Halprin reflects on demise:

Unfortunately, later performance has lost track of the intent of the score and many performers have not “gone with” the agreed upon score. […] It is significant to analyze why the score was violated as a guide to future work in scoring. I have been told that the score was too open and should have been more closed an therefore controlling. I do not agree. I do not feel that any score is too open. I feel that I overlooked several characteristics of scoring, principally:

1. The score was not visible enough to everyone involved.

2. Some of the score was kept secret because it was not completely agreed upon by management. For example, public access to beaches and the idea of varied income. This did not really turn out to be a balanced community in terms of income levels, which is what it was intended to be.

3. All the principles of the score were not understood thoroughly. For example, the notion of tight-housing clusters of various configurations was not really visualized by the sales force.

4. Early sales management groups were disbanded, and the second wave had not been involved in the score and subsequently did not really understand it.

5. Short-range economic goals were allowed to override long-term goals. (Halprin 1969, 146)

Explanatory Potential for Notation for Improvisers

What can we learn about scores and collective improvisation from the example of The Sea Ranch? What does it tell us about the relevance of the RSVP cycles to notation for improvisers?

First and foremost, scores are but a single factor in collective environments; Halprin’s model is ecological. By this I do not mean (only) that it concerns itself with the natural environment. Rather, I mean that the cycle situates its four elements in a non-hierarchical environment where their unpredictable mutual influence is made visible. Following improvisation scholars David Borgo (n.d.) and Marcel Cobussen (2016), I believe the ecological perspective to be fruitful for the study of improvised music in general because of the way in which it foregrounds the simultaneous action and perception of musicians with instruments, each other, physical and social spaces, and many other “actors, factors, and vectors” (Cobussen, Frisk, and Weijland 2010). Borgo:

When viewed ecologically, cognition is best understood as a process co-constituted by the cognizing agent, the environment in which cognition occurs, and the activity in which the agent is participating: action, perception, and world are dynamically coupled. In this light, improvisation may be seen as a cyclical and dynamic process, with no non-arbitrary start, finish, or discrete steps (i.e., it is not a token of a compositional megatype). The improviser and the environment co-evolve; they are non-linearly coupled and together they constitute a non decomposable system. (Borgo n.d., 10)

An ecological approach is suited to scores for improvisers because it shows their participation within this co-evolution, rather than their prescription or preservation of it from the outside. We must not begin at (S) and proceed directly to (P) – with an optional path through (V), interpretation and rehearsal – as would be suggested by some linear models of notation and performance (Boulez 1990, 87; Nattiez 1990, 17). The cycle may start anywhere and move in any direction; thus it accommodates how notation emerges and feeds back on ongoing improvisational practices (see “Entextualization and Preparation in Patterson’s Variations for Double-Bass“); how it changes and is changed through use (see “A Treatise Remix Handbook”); and its growth over longer periods of time – what precedes and follows an initial inscription and single performances (see the Bach example above).

A second related point is that scores and collectives are mutually influential, but ultimately independent of one another. On a positive note, the collaborative aspect of work is present in the model even when the participants, such as a composer of written texts and an instrumental performer, do not work together personally. The cycle can be shared and distributed among many parties over time and space, and the continuity and contingency of the work-as-verb is still manifest – whether this occurs between J.S. Bach, Anna Magdalena Bach, and Pablo Casals; or between Halprin, Barrett, and me. However this point reveals a potentially problematic side to notation for collective improvisation. As we see in point (10) of my mapping of The Sea Ranch project, collectives and scores tend to evolve on their own terms, and neither one can sustain the other. Group personnel, performance practices, and interest in particular scores inevitably drift; scores may only make sense in a particular constellation, or lose value after having been played only once. If a given project is inherently temporary – as in the case of Richard Barrett’s fOKT series – this may not be a problem, and even an asset. But as in the case of The Sea Ranch, the sustainability of ambitious long-term projects may be compromised or crippled by the very contingency that animates them.

A third relevant aspect of Halprin’s model is the (V) element, valuaction, “which analyzes the results of action and possible selectivity and actions. The term ‘valuaction’ is coined to suggest the action-oriented as well as the decision-oriented aspects of V in the cycle” (Halprin 1969, 2). It “incorporates change based on feedback and selectivity, including decisions” (191).

What might valuaction mean in the context of notation for improvisers? On the one hand, it may surface in processes of criticism, revision, and verbal negotiation among collaborators as we see in The Sea Ranch project. Ideas are inventoried; a score is produced; it is discussed and edited (V); fundamental assumptions and materials are reconsidered; the score is revised; the project is performed; the results are discussed again (V); and perhaps they lead to subsequent scores and performances. This is very much the case in A Treatise Remix: I studied the score of Treatise and its performance history; collected recordings and edited them into a collage; presented my collage and ideas about the score to my collaborators; discussed, rehearsed, and revised my plans with them (V); performed with them in the studio; made adjustments to the plan in the studio according to the input of my producer and sound engineer (V); assembled the live recordings with the collage in sometimes unpredictable ways; added unplanned material and erased planned material; and then returned to the studio for the final mix. This sense of valuaction is, in fact, nothing special; it inheres to virtually any workflow that admits even a modicum of change and diversity.

But valuaction can also take the form of nonverbal reflection in practice, experimentation, and rehearsal. In this context it has a strong affinity to guitarist and artistic researcher Stefan Östersjö’s notion of “thinking-through-practice” (Östersjö 2008, 77), which he develops as an alternative to the notion of performative interpretation:

It involves the physical interaction between a performer and his or her instrument and the inner listening of the composer; both of which are modes of thinking that do not require verbal ‘translation’. Instead they function through the ecological system of auditory perception. […] thinking-through-practice is an interpretative process that makes up an important part of the preparatory work leading up to a performance. And it is a process of validation that goes on also in the performance itself. (Östersjö 2008, 77-78)

Östersjö’s last point – that thinking-through-performance, or nonverbal valuaction, can continue into the performance itself – is especially significant to improvisation, where evaluation-and-action during the course of performance are not only possible, but mandatory to the performance’s very continuation. The musician hears as she plays as she hears, but this is not an unmediated flow; she might make mistakes, she interacts with one sound or player and not another, she feels ambivalence about when to end or not. These are all instances of evaluations that lead to action, and they are inherent to the activity of the improviser during performance. That Halprin’s model gives (V) the same hypothetical importance as all the other elements in the cycle underlines its proximity to the practice of improvised music.

Fourth, the model is based on activity and artifacts rather than on the functions of particular actors; identities shift with and/or emerge from the process. This is useful in the context of notation for improvisers because categorical distinctions between composers, improvisers, and interpreters are bypassed. As we see throughout Tactile Paths, such traditional divisions of labor can be difficult to establish in this music because composition, improvisation, and interpretation are often carried out by one and the same person or people (see Ben Patterson’s Variations for Double-Bass or Bob Ostertag’s Say No More). Even when these activities are carried out by separate subjects – as for example in Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise (1967) or my Apples Are Basic (2008), where the composer notates and others play – the actual work of composing and performing overlaps considerably; the practice of improvisation occupies a space between them. As I show throughout the dissertation, following experimental musician and scholar George E. Lewis,

[c]reating compositions for improvisers (again, rather than a work which “incorporates” improvisation) is part of many an improviser’s personal direction. The work of Roscoe Mitchell, Anthony Braxton, John Zorn, and Misha Mengelberg provide examples of work that retains formal coherence while allowing aspects of the composition to interact with the extended interpretation that improvisers must do – thus reaffirming a role for the personality of the improviser-performers within the work. (Lewis 1996, 113)

The cycle thus allows us to focus on workflows unique to particular projects or performances. It not only generically frees us from problematic conceptual binaries, but also provides a view of what specifically emerges in its place on a case by case basis.

This aspect of Halprin’s model may have had its roots in the social structure of his profession. As a landscape architect, Halprin would never – indeed could never – have operated as solitary author, or considered his collaborators as executants. He was constantly required to negotiate with other architects, investors, politicians, urban planners, climatologists, geographers, engineers, contractors, and (sometimes) even ordinary citizens, and his work changed drastically in the process. We remember that, for better or worse, the RSVP cycle bound him with The Sea Ranch architects, engineers, planners, et al in a dynamic process together.

Indeed this brings us to the political heart of the model. By making visible the creative process itself, rather than a chain of command, Halprin proposed to subvert the top-down decision making behind product-oriented thinking, which consolidates power and dehumanizes end users – in his case, communities who inhabit planned urban environments:

If the scorer develops a closed, completely precise score, he then assumes complete responsibility. In the newer “open” scoring, members of the audience as well as performers often participate in performances. As a result, they need to recognize that in these instances responsibility is shared by them. The new scoring needs to be as visible as possible so as to scatter power, destroy secrecy, and involve everyone in the process of evolving their own communities. […]

A community has the right to make scoring decisions itself, based on its own understanding of the implications of action. The implication of this method of approaching planning through multivariable scoring systems is not to abrogate authority or decision-making in deference to chaos, or to avoid responsibility by making everyone responsible. What it proposes is a scoring process related to parts of the “systems approach” in operational research where all the parts and participants, in the search for solutions to particular problems, have equal validity and strength in arriving at decisions. It is on this approach rather than a hierarchical structure of planning that the new scoring technique bases itself. (Halprin 1969, 175)

Ironically, Halprin’s very faith in the transformative power of “the newer ‘open’ scoring” (175) – particularly that of his own model – reveals its Achilles’ heel. While the RSVP cycle privileges collective dynamics over a top-down chain of command, it also fails to represent the fact that not all participants necessarily have an equal say in the process. Halprin’s dismissal from The Sea Ranch project by managers at Oceanic brings this point home bitterly.4 The owners’ unilateral abandonment of the development’s founding ecological principles reminds us that nominal collectivity in notation is no guarantee of symmetrical power relationships or real collaboration.5 Even if the score had been more visible to Oceanic, as Halprin wished in his last valuaction (1969, 146), it is unlikely that The Sea Ranch’s corporate owners would have held the score’s principles in higher esteem than their own bottom line.

Though The Sea Ranch was in many ways a successful and artistically groundbreaking project, Halprin’s liberatory model of notation, and my proposal at the beginning of this chapter seems in this case to have failed.6 Returning to the proposal with which I began this chapter,

Score + Response = Collaboration ≠ Liberation.

As ever, one must look beyond notation to the contingent particulars of its use. Apropos, let us now turn to the music of Richard Barrett, and explore his concrete use of notation for improvisers in the framework of the RSVP cycles.

Richard Barrett

A brief introduction to Barrett’s unique artistic trajectory will help us situate his work. In contrast to many artists working with notation for improvisers, Barrett has been active at the extremes of “straight” new music and experimental improvised music for most of his career. His catalog of through-composed chamber, orchestral, and electronic music includes over 120 pieces; they have been played by some of the most prestigious soloists and ensembles in the field. Since the mid-1980s, he has also frequently performed as an improviser on electronics. Of particular importance in this vein have been his long-term collaboration with Paul Obermayer in the duo FURT and his work with the Evan Parker Electroacoustic Ensemble. Recent performances and recordings in trio with violinist Jon Rose and contrabassist Meinrad Kneer, and in the Belgrade-based collective Studio6, round out the picture.

His work in both areas shares many aesthetic traits: rhythmic irregularity and hyperactivity; dense, intricate textures; constant shifts of pacing and perspective; and precise, jagged formal architectures. However, until the late 1990s his public activities as a “composer” and as an “improviser”7 were surprisingly discontinuous, if not to say mutually exclusive. On the one hand, his through-composed music from this time employs elaborate conventional notation, noteworthy for its rhythmic and timbral complexity and technical virtuosity. The scores’ high information content indexes Barrett’s use of post-serial mathematical and scientific models that often affect every parameter of musical expression. Superimposed indications relating to timbre, articulation, dynamics, rhythm, and gesture sometimes contradict each other, producing “ambiguities, imperfections, contradictions, and so on, which constitute what might be called the ‘poetry’ of notation” (Barrett 2002b). One may surmise that notation is essential to the creative process in these pieces both for the structural precision it enables at the compositional level and for its unpredictable effects on performance.

On the other hand, his trajectory as an improviser through the end of the 1990s seems to have been marked by a commitment to the radical contingencies of that medium: the situatedness of the moment, for which no additional notation or articulated plan is necessary. Barrett:

I would characterise what has become called ‘free improvisation’, or ‘non-idiomatic improvisation’ (to use Derek Bailey’s formulation), as a method of musical creation in which the framework itself is brought into being at the time of performance, rather than existing in advance of it. […] The possibility of improvising the structural-expressive framework of a piece of music comes into being, I think, as a direct consequence of the realisation that any sound may be combined with any other sound in a musical context. After this point, there is no further need to create or inherit the framework in advance of making the music – although of course there may be a desire to do so, for many possible reasons. (Barrett 2014, 2)

Barrett hastens to note that in his view the spontaneous emergence and re-working of improvised music’s structural-expressive framework in performance does not “just happen” (2002b). As do most contemporary improvisation scholars, he qualifies this immediacy by stating that it “depends to a crucial extent on external and internal conditions” such as tradition (Barrett 2002b). Although Barrett, pace guitarist Derek Bailey (1993, 83), distinguishes free improvisation from improvisation within “fixed and/or pre-existent framework[s]” (2014, 62) such as baroque music or jazz, in fact Barrett’s improvisational trajectory has centered on a rich microtradition of its own in FURT. Over the course of several years of working together, the duo has evolved not only a “group sound” in the general sense, but also a tightly coupled way of working reflected in shared tools8 and sample libraries. Barrett and Obermayer:

We tend to think of FURT as one person rather than two; while our musical preferences and activities outside the duo don’t coincide precisely (though almost), in a FURT context they do, so that for the most part disagreements don’t occur. One of its most important aspects is that it encourages both of us to think in terms of more extreme ideas, or solutions to musical issues, than we would do individually or in playing with others. […] We mix our performances from the stage, and fiddle around with each other’s output levels without bothering to ask. Synchronisation is one of those things which takes its course; both of us deciding simultaneously to do something, or to change something, or to stop something, can be taken for granted as an outgrowth of the general symbiotic situation which obtains in a FURT performance. (Barrett and Obermayer 2000)9

Thus, one may gather that, in the era before he worked with notation for improvisers, Barrett’s moment-centered view of the structural-expressive framework of improvisation included collaborative relationships developed over time.

Barrett’s Notation for Improvisers

With transmission IV (1999), the fourth of six movements for solo stereo electric guitar and electronics, these two strands of Barrett’s musical life began to intertwine on the page. The score looks much like its through-composed antecedents, with one major exception: between the densely notated fragments, the guitarist may improvise.

The lacunae may be occupied by silence and/or improvisation. Improvisations may or may not be extrapolated from the notated material (or the notated or improvisational playing of the other performer, or even material from outside the work, though the latter option should be approached with the utmost care and sensitivity), and are completely free with respect to timbre, dynamic and so forth. (Barrett 1999, introductory notes)

In an essay on CONSTRUCTION (2011), a cycle of pieces that contain strategies similar to those explored in transmission IV,10 Barrett locates the origins of his engagement with notation for improvisers in a profound experience of performing Cornelius Cardew’s The Great Learning (1972). Cardew’s mammoth verbally notated work, based on texts by Confucius, was written for the Scratch Orchestra,

an experiment in collective musical creativity of which Cardew was a founder member and whose aesthetic identity was to a great extent defined by The Great Learning. This work consists of seven paragraphs corresponding to the division of the original text, and the longest of these is Paragraph 5 […]. The second half of Paragraph 5 is a free improvisation […].

Something that stuck in my mind about this experience was the way that this improvisation, despite being in many different senses “anarchic”, was somehow informed and imbued with particular qualities by the actions which preceded it, and by their disciplined nature, without Cardew having had to say anything in the score about how the performers should approach it. […] This seemed to me, as it no doubt seemed to Cornelius Cardew, to be trying to say something about how a society in balance with itself might become self-organised, so that the idea had resonances far beyond addressing the relationship between improvisation and preparation in narrowly musical terms. (Barrett 2011)

Barrett’s turn to notation for improvisers was thus motivated not only by technical or aesthetic concerns, but also by political ones. The social relationships within collective music making – what Born calls the “microsociality” of performance (2016, 52) – were the crux of that turn. Barrett aimed for contingent performer choice not merely to shape the musical structure, but to co-constitute it:

a composition will have clarity without being defined in advance to the point of giving instructions to performers, instead providing the performer with a precisely imagined common point of departure and thereafter leaving them to use their imagination and responsibility. (Barrett 2011, 1)

Regarding this point, we see a number of clear connections to Halprin’s motivation for developing the RSVP cycles. Both Barrett and Halprin take pains to distinguish their views from chaos and anarchy; both emphasize the responsibility of participants; and both caution against the destructive potential of determining results in advance of the process. In many ways, their ideas on the nature and power of notation in collective creativity fit hand in glove.

Nevertheless, their deliveries differ. The RSVP Cycles is saturated in the idealism of 1960s San Francisco counterculture, and the communalism that Halprin sought to bring to The Sea Ranch from his experience on a Kibbutz. A close parallel can be found in the work of designer, systems theorist, and fellow “hippie modernist” (Castillo 2015) Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983). By contrast, Barrett’s edgier approach bespeaks his coming of age in – and overt resistance to – the repressive conservatism of what Derek Bailey has called the “Thatcher Winter” (Bailey 1987), during which many of the UK’s public services and cultural funds were systematically dismantled.11 Such connections are hard to miss in Barrett’s head-on critiques of the musical culture in which the microsociality of his music is embedded. The following conclusion of an essay on Blattwerk (2002a) is, for its frankness on this subject, worth citing in its entirety:

Finally I would like to return to my reasons for wanting to explore regions beyond the purview of the 20th century composer/performer relationship. My reasoning could be summarised as follows:

(1) My personal experience of listening to contemporary music is that, with few exceptions, the art of composition, as it is “understood” by the institutions which purportedly exist to promote and nurture it, is moribund in comparison with what is being achieved and developed in the context of improvisation.

(2) I believe this exhaustion in the world of composition has straightforwardly political roots in the way that the accepted social model of this art mirrors the structure of the society which generates it, that is to say, it is characterised by dehumanising economic/power relations. It is therefore no wonder that composers (to name only these) seem to have only two choices before them: to capitulate to commercial interests and become small-business entrepreneurs in the music industry, or to turn inwards, towards a “group-solipsism” where they and their peers can convince each other that their creative impoverishment is actually something vital and significant. I feel it is necessary to reject both of these standpoints as different forms of fin-de-siècle pessimism, neither of which can produce a visionary art worthy of the potential of human imagination and intelligence.

(3) Nevertheless, there is nowhere else to go; and, as I hope to have made clear, I believe that the art of composition in the widest sense is not exhausted. Most of the work I have done in recent years has had as a fundamental motivation a search for ways to “make it work”, in the context of various collaborative and collective musical activities. This isn’t the place to enumerate these activities, nor is it yet the time, at least for me, to assess them. For the present I would merely like to suggest that Blattwerk is intended to take its place in this process, or at least in defining some potential directions it might take. Every musical score embodies a question, to be answered by its performer(s). (Most composers seem only interested in receiving the answer YES.) What I am trying to do here is put that question in the musical foreground, in the hope that when the performer makes his/her music in response to it, some opening-out of the imagination comes into being which might not have occurred in other circumstances, and in the hope that this process communicates itself to activate the imagination of the listener. This may seem like a tall order; but in the words of Edward Bond, “clutching at straws is the only realistic thing to do.” (Barrett 2002b)

Despite the overall acrimony of this text, Barrett presents a ray of hope in point (3) that brings us back to the proposal I outlined in the introduction to this chapter: “a question, to be answered by its performer(s)” – an invitation to collaborate on something in particular. By conditioning the open-ended processes in his notation for improvisers with a “precisely imagined common point of departure” (Barrett 2011, 1), or “seeding” them (see Barrett 2014), he goes a step further than clutching at straws. He takes responsibility for his authorship – making his own position visible – and addresses what I consider to be the major problem with the RSVP cycles: its failure to represent power relationships.

On that note, we now turn to a case study for a new proposal:

Invitation + Question + Response = Collaboration = Liberation (?)

FURT, fORCH, fOKT

1. (R)

The first three installments of fOKT (2005) were written for a bespoke ensemble of eight improvisers entitled fORCH.12 The genealogical origin of the project can be traced to FURT, Barrett’s electronics duo with Obermayer:

fORCH was initially formed, at the invitation of Reinhard Kager,13 for the 2005 New Jazz Meeting of the SWR (South West German Radio), which consisted of a week of intensive rehearsing and recording followed by four concerts. […] Expanding FURT into a new kind of “orchestra” (hence the name fORCH) had been an objective for many years, and the SWR project created an opportunity to establish such an ensemble, in which the electronic duo was combined with vocalists and instrumentalists, all leading players in the world of improvised and experimental music who have developed their own unprecedented sounds and techniques. (Barrett and Obermayer 2009)

The players chosen for the SWR event – which included four concerts in Baden-Baden, Karlsruhe, Basel, and Stuttgart – were John Butcher (saxophones), Rhodri Davies (harps), Wolfgang Mitterer (prepared piano), Paul Lovens (percussion), Phil Minton (voice), Ute Wassermann (voice), Richard Barrett (electronics), and Paul Obermayer (electronics). As Barrett and Obermayer note, all of these musicians were experienced improvisers; two of them, Lovens and Minton, had rarely worked with notation.14

The ongoing practice of FURT; Barrett’s wish to expand its principles to fORCH; the rehearsal phase and concert tour made possible through the SWR New Jazz Meeting; and the ensemble members’ backgrounds all form the initial (R) of the project. It is important to note that they do not behave as discrete items on a list. Rather they form an integral situation from which subsequent steps in the cycle emerge. Just as the personnel, landscape, creative wishes, and history of The Sea Ranch were dynamically linked, so do the components of (R) in fOKT condition the next step in the cycle together. Some of those conditions:

- A long, intensive rehearsal period meant the score would not need to be comprehensive; there would be plenty of time for personal communication and experimentation.

- The score(s) would need to be written in a way that Minton and Lovens would respond to – i.e. not in conventional notation – if they were expected to pay it any heed.

- The players would all bring their diverse, idiosyncratic methods and sound worlds to the piece. The ensemble would therefore not only passively extend FURT’s history and identity, but also actively transform and potentially confront it.

2. (S) – Entextualization

The first three scores for fORCH, fOKT I-III (2005), were prepared by Barrett before the week of rehearsal in Baden-Baden. Though each was meant to be performed on a separate concerts of the tour – they comprise a unified bundle. Each score makes use of a similar notational format and refers to the same legend, instructional modules, and musicians. According to Barrett, “the first set of fORCH scores served to short-circuit a process whereby FURT’s aims and methods would infuse the whole group” (Barrett, personal email to the author, 5 August 2016). The scores of fOKT I-III can thus be considered an entextualization of FURT’s improvised praxis.

In my chapter on Ben Patterson’s Variations Double-Bass, I introduce the term entextualization as “the ‘process of rendering a given instance of discourse as text, detachable from its local context'” (Barber 2007, 30). In fOKT, as in Variations, improvised discourse precedes the written score; it is therefore important to consider how the score reflects and mediates rather than defines it.

What aspects of this praxis are entextualized, and how? To begin with, we may note some superficial traces. One of these is the predominance of vocal material. As Barrett and Obermayer note,

A constant strand in our output has been the appearance of diverse vocally‐derived materials, using our own or sampled voices, which seem primarily to be engaged in the (often desperate) attempt to articulate a message whose import remains out of reach. (Barrett and Obermayer 2000)

Ute Wassermann and Phil Minton are, of course, no ordinary singers. Their extraordinary command of noisy and extreme vocal techniques is a fundamental part of their work as improvisers, which both complements and extends FURT’s virtual manipulations of vocal samples.

Another immediately recognizable mark of FURT on fOKT’s notation is the fact that Barrett and Obermayer nearly always play together; I recall their comments on synchronicity (2000) when remarking how much more often their modules coordinate in comparison with the parts of the other musicians.

Barrett’s use of physical gestures to cue other players is a third entextualized element. Barrett and Obermayer:

Extra‐musical communicating in performance generally involves one of us reminding the other that something important ought to be about to happen. We did have a repertoire of signals, which were eventually discarded because they were never used. (Barrett and Obermayer 2000)

Although these signals may never have entered FURT’s microtradition, the group’s “attempt to articulate a message whose import remains out of reach” (2000) seems to be embodied in Barrett’s highly kinetic presence on stage.15 This is extended into fOKT not only through hand signals at the beginning or end of larger sections, but also in “coordinated modules” (see below) where Barrett and other members of the ensemble gesture to musicians spontaneously to trigger textural changes.

FURT’s aims and methods are most deeply and dynamically reflected in fOKT‘s timeline-based score, with “tracks” that correspond to each player. The track notation shares in common with conventional notation a vertical distribution of parts that correspond to particular voices; players read their tracks from left to right. But unlike in conventional notation, material consists not of pitches, rhythms, and specified sound events, but rather of modules that refer to eight event types within which the players improvise for a rough duration.

Event types include (1) Textures, which “describe a point of arrival or departure for a process” detailed on a case by case basis; (2) Duos, which link specific players as a subgroup within the ensemble playing one of two loosely defined material types; and (3) Coordinated Events, in which Barrett’s “unambiguous hand signal[s]” cue different types of designated behavior from “explosive bursts” to guided solos that suddenly change character. Event types (5-8) refer to microsocial relationships of a given player or subgroup to others in the ensemble. This category includes (4) Solos, (5) Accompaniments, (6) Perturbation, and (7) Transitions. Free improvisation is also included, represented by an infinity symbol (∞). (1-3) are often combined with (5-7).

Specific modules refer to sound objects (T4: Points – “almost exclusively short sound with longer silences between”, or D3b: “breathy and consonantal sounds”); individual processes (Transitions – “gradual or stepwise transformations within or between any of the other types of activity”); and socially distributed processes (A: “as it were the opposite of Solo […] affected by everything else which is going on at that point relating”). These are often combined in a single module such as C3:

C3: Ute/John/Phil: begin sustained, interwoven sound at first cue (like T3 “submerged” material but generally louder); everyone changes sound (in timbre, pitch etc.) instantaneously at each cue as if switching between radio stations or CD tracks.” (Barrett 2005, “Coordinated Events”)

That the modules’ material, subjective, and intersubjective modalities overlap is a distinguishing feature of fOKT’s notation. Timeline-based notations in general are common in notation for improvisers (see Bob Ostertag’s Say No More, Werner Dafeldecker’s Small Worlds (2004), or John Butcher’s somethingtobesaid (2008)). Asking performers to “do what you want here! And stop around here!” with loose guidance, as Minton suggests (see fn. 14), is indeed a practical and transparent way to compose for and/or with musicians who may not work, or wish to work, regularly with notation. But whereas Ostertag’s, Dafeldecker’s, and Butcher’s timeline notations simply describe who should play with whom and/or roughly what kind of material should be employed at a given point, Barrett’s case is more complex than Minton suggests.16 The majority of Barrett’s modules ask each performer to be aware of several levels at once (much as his through composed music does), and often multiple modules occupy the ensemble simultaneously. This results in a meshwork of cross-referenced sounds and contingent processes, potentially tethering the players in subtle and unpredictable ways.

The multidimensional aspect of the modules reflects and extends FURT’s unique approach to sampling, in which multiple layers of sound objects are processed in real time, often beyond recognition. Barrett and Obermayer explain their first discovery of samplers in 1986:

Sampling was obviously the way to go ‐ but, crucially, with the purpose of extending (as far as our imaginations would stretch) the accessible sonic repertoire of the duo without dragging around a truckload of instruments and growing several extra arms each, rather than buying into a postmodern world of undigested quotation. That was clear from the start, and has become ever more clear; once a sampled sound has found its way into a FURT performance we seldom have any idea ourselves as to its origin. Sometimes we sit around at home listening to a CD and are shocked by the surprise appearance of a FURT sound in somewhat unfamiliar (ie original) form. (Barrett and Obermayer 2000)

In fOKT the modules act as conceptual “samples”, assigned to the performers who “process” the material according to their own radically different methods and sound worlds. When multiple modules are played at once, and begin and end at different times, their individual identities are positioned for scrambling in the dynamic polyphony of the whole. The kaleidoscopic mashup that is likely to ensue – a FURT trademark – is different in kind from the effects of notation and sampling in Say No More, for example. Despite all the ways in which Ostertag distorts and recontextualizes material through processing and transcription, he maintains the identities of the four instrumental voices consistently. Furthermore, he reinforces their integrity through a vocalist/rhythm section dynamic – something rather unthinkable in fOKT, where individual identities are perpetually refracted.

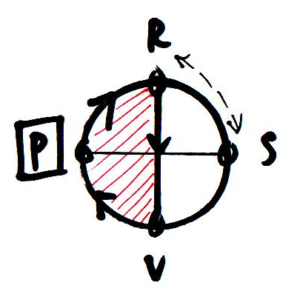

3. (R) = (R0 → V0 → P0 ↺) – Remapping

Considering the particular process that the score entextualizes, it is somewhat misleading to map fOKT‘s first steps on the cycle simply as (R) → (S). A richer and more exact mapping nests aspects of FURT’s ongoing practice in (R) directly. FURT’s practice constitutes its own ur-cycle, which does not use written scores: (R) → (V) → (P):

- (R): sample library, jointly chosen instruments and software, synchronicity and duo history

- (V): preparation and experimentation with samples, individual live processing and decision making process during performance

- (P): collective improvisation in concert

Adding subscript 0 to designate that the ur-cycle is prior to fOKT, and a sign to denote that the cycle is repeated (↺), we have (R0 → (V0) → P0 ↺). If we nest this ur-cycle back in (R) and combine it with (S), its entextualization, we obtain the following new mapping:

What this operation makes visible is that the feedback of FURT’s microtradition remains in movement, and the score emerges from it: an invitation to collaborate on a concrete question. This is a far cry from modeling the first stages of fOKT‘s inscription as the linear process (R) → (S), which suggests that (R) becomes frozen or absent during (S). Neither of these is the case, as FURT’s work grew from within the process of composing and performing fOKT; indeed one may infer from Barrett and Obermayer’s comments that this was precisely the point of the project.

4. (V) – Rehearsal

In my discussion of the explanatory potential of The RSVP Cycles above, I claim that in order to understand the social dynamics of a score for improvisers, one must look beyond notation to the contingent particulars of its use. In the case of fOKT‘s rehearsal process, (V), this is a difficult standard to uphold. I was not myself a performer or composer of fOKT (as I am in most pieces included in Tactile Paths), nor did I perform ethnographic research in Baden-Baden in the week prior to the premiere. Furthermore, there is no extant documentation of this phase to work with (as there is for The Sea Ranch). I shall thus offer a few brief speculations on what (V) might have entailed, working forward from the structure of the notation and backward from subsequent steps that I can observe in recordings.

The performers, we can assume, began the project with the score. This can be inferred from the fact that Barrett had prepared the score in advance, and that the project as a whole had no previous history or “shared language” to build upon. (Most of the players, however, had worked together in different constellations before, so a certain degree of mutual familiarity would have been in play.) Since the recordings of fOKT II and fOKT III correspond fairly closely to the structure specified in the score, we can also assume that the players worked with the notation in good faith.17

The notation is sufficiently complex that it would have required the performers to study the score, both in order to memorize the nomenclature, and to understand how their own modules linked to other players. But the pace of change between the modules in individual parts is not so fast that it would have required substantial, if any, individual practice. Barrett was of course also present during rehearsals as a performer, so other performers might have shortened the learning curve by clarifying doubts with him personally. Indeed, it seems clear that the notation is geared toward group learning, and (V) would have occurred mostly in the context of playing together.

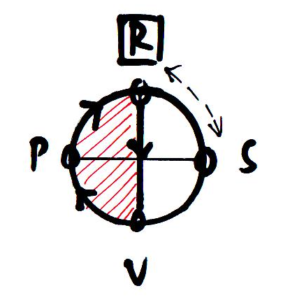

5. (P) = ((S → R) → (V → P → R ↺) ↺) – Recontextualization

Here I would like to address how ensemble performance of fOKT traverses the RSVP cycle in both rehearsal and concert performance. In the same way that I nested FURT’s ongoing microhistory, or ur-cycle, in (R), it seems appropriate to nest another feedback loop in (P). We assume again the performers start with (S).

In a conventionally notated score whose material is given, performers generally proceed to (V) (in dialogue with (R)) on the way to (P), as I explain in my expansion of Halprin’s Bach example. Even though Amirkhanian’s graphic score Serenade II does not prescribe materials, it shares the same path, for according to him and Halprin its indeterminate symbols are in any case semantically “interpreted” directly as sound and action. While the bandwidth of possible interpretations is perhaps wider in Serenade II than in the Bach example, movement on the RSVP cycle is the same in both cases.

fOKT is different because of the multivalent nature of its modules, in which players choose the material themselves. The path therefore first passes back through (R). (R) here consists not only of the inventory of conditions that I mention above, and FURT’s ongoing practice, but also the resources of the ensemble. What do these include?

First and most obviously, they include the individual performers’ resources: the unique embodied sound worlds and methods for which they were invited to participate in the project in the first place. Even where material is given in the score – and sometimes, as with pure18 event types (4-7), it is not – it is so loosely defined that it acts more as a suggestion or filter on the performers’ own material, rather than as a prescription per se.

Second, if the performer does not begin the piece with a solo (as Davies does in fOKT II), unpredictable activity in the rest of ensemble will also constitute an element of (R). To be sure, group interaction is usually present in any collective improvisation, but its centrality is unavoidable here when the score couples players to cues, specific subgroups, and group textures.

A third aspect of (R) within (P) is the evolving performance practice of fORCH itself, or what percussionist and composer Burkhard Beins’ calls “collective spaces of possibility”:

Collective spaces of possibility already begin to establish themselves when the same group constellation meets for a second time after having formed some initial common experiences. Through continuous collaboration and by being repeatedly revisited […] their shape and content become ever more clearly defined and increasingly differentiated. This phenomenon appears to take place whether those who are involved are actively aware of it or whether they tend towards appreciating or rejecting such developments. (Beins 2011, 171)

Without my having been present with the musicians in 2005, it is difficult to assess how the microtradition of fORCH emerged (or how it was fORGED so to speak), and “whether they tend[ed] towards appreciating or rejecting such developments” (Beins 2011, 171).19 However it seems fair to assume that the intensive rehearsal period and concert tour would have fostered a collective space of possibility that was at least recognizable. It is telling and poetic in this sense that Barrett and Obermayer begin the performance fOKT III with samples of what sounds like a fORCH performance from the previous days.20

From (R), performers proceed to (V) on the way to (P). As I mentioned earlier, valuaction for an improviser can take place in real time as she mediates what she hears as she plays. In fOKT, (V) serves this function as well as managing the implementation of processes that pass through (R). That is, the performer simultaneously evaluates and acts on both the contingent and empirical aspects of (R) I mention above, and the indications of the score that condition them. This dual function of (V) may manifest in simple tasks, such as checking in with the timeline in the middle of an ongoing module. Due to the internal multivalency of the indications themselves, it may also manifest in more complex tasks, such as negotiating when to make a given transition, or how to “ignore” another performer who is instructed to “interrupt” (see Wassermann’s and Minton’s first modules in fOKT I).

(P) itself may be thought of as a complex intersection and recontextualization of all the paths I have just described: the concrete materialization and interaction of individual (R)s and (V)s. The richness of this step in the cycle, the musical “now” so to speak, again challenges Halprin’s own characterization of his model, in which he defines performance as “the resultant of scores and […] the ‘style of the process'” (Halprin 1969, 2). His definition suggests a linearity and fixity which, in my opinion, is fundamentally at odds with the dynamic structure of both the cycle and performance. After all, if one conceives of performance as the end of the cycle or a mere “style of the process”, the RSVP cycle might as well be an RSVP line segment.

In fOKT, and indeed in all improvisations, what comes out of the process goes back in. Every sound and action produced in performance becomes a new resource for the group, to be valuacted upon by others. As a performance goes on, and as performers become more familiar with the mechanism of the score in repeated rehearsals and performances, the notation is likely to recede. For as in any written piece of music, the cumulative process of internalizing rules and relationships represented by (or in this case entextualized in) the notation renders the representation itself increasingly redundant. The score gradually becomes a satellite, a possible resource for ongoing improvisation:

6. (R) = (R → V → P ↺) → (S?) – fOKT IV-VI (2007-2009) and spukhafte Fernwirkung (2012)

The central feedback loop that occurs in (P), (V → P → R ↺), has also occurred over the life of fORCH; the ensemble’s “collective spaces of possibility” (Beins 2011) – its microtradition – has outgrown both the overt influence of FURT and the use of elaborate notation. As one may see, the scores of fOKT VI and spukhafte Fernwirkung (co-composed, it should be noted, with Obermayer) are so bare as to be hardly necessary; like Barrett’s codex VII, they serve more as mnemonic devices than as genuine interfaces. Minton’s recollection of spukhafte Fernwirkung is revealing: “From what I can remember of richard and pauls [sic] piece it was like above [“do what you want here! And stop around here!”] and all the cues where [sic] audio” (Minton, personal email to the author, 2 August 2016). The role of notation in these projects was so minor, in fact, that Barrett was unable to fulfill my recent request for a copy of fOKT V because he had lost them! Nonetheless Barrett and Obermayer have remained members of the ensemble, and fORCH, in theory, lives on.

Conclusion – Valuaction

What lessons about notation, improvisation, and collectivity can we draw from the examples of fOKT and The Sea Ranch? In both cases, scores “energize” the collective creative process (Halprin 1969, 191); they stimulate and condition group interaction. However the nature and degree of the notation’s impact on the process changes over time. At the beginning of the process, scores tend to have a more active role, directly mediating interaction between individual participants, or between the participants and other contingent elements of their performative environments. As the process evolves over time, however, activity energized by the score takes unpredictable turns and follows its own trajectories. That unpredictability stems not only from microsocial dynamics within the group, but also from factors not represented in the score – particularly the higher order socialities in which the creative process is embedded. Local feedback between participants becomes enmeshed with larger-scale environmental feedback, generating situational structure that diminishes the importance of the notation. Nevertheless, participants still use scores to agitate and reflect on the process in later stages.

The consequences of these principles, with respect to the political issues touched upon in this chapter, were very different for fOKT and The Sea Ranch. On the one hand, Halprin was forcibly removed from the creative process he set in motion by a participant whose power was not represented in the entextualization of that process; the motivation for his removal was greed. The main resource produced through the performance of the process – The Sea Ranch itself – was thus severed from Halprin’s ecological principles and lost much of what made it a humanistic endeavor and profoundly original work of art. The Sea Ranch lives on, but its legacy is ambivalent. In a 2013 reflection on their work together, Halprin’s fellow The Sea Ranch architect Donlyn Lyndon asks,